2020 Global Health 50/50 Report

Power, privilege & priorities

The 2020 report provides an unprecedented birds-eye view of the global health system today. It reveals that the leadership of the 200 most prominent organisations active in global health continues to reflect power and privilege asymmetries along historical, geographic and gender lines. The report further uncovers a distinct disconnect between the organisational priorities and the gendered burdens of disease around the world.

The report warns that these inequalities -- an inequality of opportunity in career pathways inside organisations and an inequality in who benefits from the global health system -- are impeding progress towards health goals.

Explore the report

Power, privilege and priorities

Foreword

A word from Michelle Bachelet

United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, former President of Chile

Preface

A word from the Global Health 50/50 Collective

About the report

The third Global Health 50/50 report reviews the gender-related policies and practices of 200 organisations. These are global organisations (operational in more than three countries), that aim to promote health and/or influence global health policy.

The 2020 report deepens GH5050’s annual analysis by adding new variables on power and privilege within organisations. These variables include: workplace diversity and inclusion policies, board diversity policies and additional demographic information about executive leaders and board chairs. It also compares the health priorities of 150 organisations against the health-related targets of the SDGs and the global burden of disease, to identify which issues and populations aren’t getting sufficient attention.

Find out more about the reportPower

The ability to influence and control material, human, intellectual and financial resources to achieve a desired outcome. Power is dynamic, played out in social, economic and political relations between individuals and groups.Privilege

A set of typically unearned, exclusive benefits given to people who belong to specific social groups.Priorities

Those issues and populations towards which political and financial resources are allocatedOur findings

Commitments to redistribute power

Public commitment to gender equality

Organisations report a fast-growing commitment to gender equality and social justice

GH5050 reviewed the visions, missions and core strategy documents of organisations to identify commitments to gender equality and to social justice more broadly.

Findings

75% (149/200) of organisations publicly state their commitment to gender equality in their mission, vision or major strategies.

Are organisations publicly committing to gender equality?

While 75% of organisations commit to gender equality, some sectors perform better than others…

One-fifth are silent on gender

The perception that gender is not relevant to organisations’ core work, regardless of their field or industry, appears to be shifting: from 2018 to 2020, the proportion of organisations that are silent on gender decreased from 32% to 17%. However, nearly one out of five organisations in our 2020 sample have yet to publicly state their commitment to gender equality.

Organisations are increasingly committing to gender equality 55% in 2018 76% in 2020

Definition of Gender

Organisations report a fast-growing commitment to gender equality and social justice

Defining gender in a way that is consistent with global norms is a political act. It confronts efforts around the world that try to manipulate the term, hijack it or erase it entirely. Anti-gender movements are visible across most regions. Their core assertions-particularly that the very concept of gender sows confusion and destabilises the traditional family and the natural order of society-have been embraced and recited by leaders and political parties at the highest levels of power.

In this contested environment, organisations active in global health or health policy must be clear and consistent in their definition of gender as a social construct rooted in culture, societal norms and individual behaviours.

Understanding gender as a social construction (rather than a biological trait, for example) allows us to see the ways in which gendered power relations permeate structures and institutions, and thus begin to address the distribution of power across and within societies, institutions and organisations. A gender lens transforms technical agendas into political ones.

Findings

While we see a growing commitment to gender equality, the meaning of gender remains undefined by the majority of organisations under review.

Just 35% of organisations (70/200) define gender in a way that is consistent with global norms (see glossary for definition). This proportion has changed little since 2018. An additional 11% of organisations define gender-related terms (e.g. “gender diversity”) but do not provide a definition of gender in their work. Only 18 organisations have definitions that are explicitly inclusive of non-binary gender identities, including transgender people.

Among the organisations reviewed since 2018, a slight increase of 6% in those that define gender has been registered: 9 organisations have added a definition of gender to their policies or websites.

Too few organisations are providing a definition of gender

Of those defining gender, how do different sectors perform?

No funding agencies publicly define gender

Key takeaways from our findings

Policies to tackle power & privilege imbalances

Policies to promote gender-equality in the workplace

60% of organisations have workplace gender equality plans

Gender plays an important role in career trajectories. Organisations in the global health sector ought to lead on justice and fairness, but male privilege pervades. This leads to a paucity of women in senior roles. Support for gender equality in the workplace means fostering a supportive organisational culture for all staff and requires corporate commitment, clear policies, specific measures particularly at times of career transition points, and accountability for redressing structural barriers to women’s advancement.

GH5050 assessed which organisations are translating their commitments to gender equality into practice through action-oriented, publicly available workplace policies. It identifies which organisations go beyond minimum legal requirements and implement affirmative policies and programmes with specific measures to actively advance and correct for historical inequalities.

Findings

Do organisations have workplace policies in place that promote gender equality?

Certain sectors perform much better than others on having policies in place

Nearly 60% of organisations reviewed have workplace gender equality policies which contain explicit targets, strategies and/or plans. One-quarter of organisations had no commitments or policies of any kind.

Among the sample of organisations reviewed over three years, progress has been made. In 2020, 69% had workplace gender equality policies (up from 57% in 2019, and 44% in 2018). Thirty-one organisations appear to have adopted, enhanced and/or publicly released their workplace gender equality policies in the past two years.

Workplace diversity and inclusion policies

At the intersection: workplace gender equality policies outnumber broader diversity and inclusion policies

Gender provides one lens through which to understand inequalities in who wields power and enjoys privilege. Gender is always in interaction with other social identities and stratifiers. Privilege and disadvantage in the workplace filters through these intersectional identities. Building a diverse workforce means recognising these intersections and developing solutions that benefit all people.

Advancing diversity and inclusion requires clear policies, deliberate focus and sustained action. GH5050 assessed which organisations had publicly available policies that committed to advancing diversity and inclusion in the workplace-alongside and beyond gender equality-and had specific measures in place to guide and monitor progress.

Findings

44% of organisations have committed to promoting diversity and inclusion in the workplace and have specific measures in place.). One-quarter of organisations reviewed make no public reference to non-discrimination, or diversity and inclusion (D&I).

Do organisations have policies in place to promote diversity and inclusion more broadly than gender?

How do different sectors perform?

Board diversity policies

A fraction of organisations have board diversity policies in the public domain

Advancing diversity in governing bodies is an issue rooted in principles of power, representation and equity.

Boards of directors are arguably the most influential decision-makers in global health. They often nominate an organisation’s leadership. They help to determine goals and strategy. Yet continued lack of diversity in boards means that they are missing the perspectives of key stakeholders, including the communities they are meant to serve.

Globally, gender diversity on boards is increasing. Progress is likely due in part to growing regulation around the world. Some countries have set strict quotas for women’s board representation in public and state-owned organisations.

In general, strict regulation on diversity is associated with more gender-diverse boards. Strong regulations are in place in many of the countries with the highest percentage of female board members. Those with less stringent regulations or no mandates tend to have fewer women on boards [ref]. However, social norms often drive the regulatory framework, and how that regulatory framework is fulfilled-thus societies that are already more gender-equal may be more likely to have stronger regulations in place.

Findings

Just 28 organisations (14%) have policies available in the public domain that state how they seek to advance diversity and representation in their governing bodies.

These 28 organisations are almost four times more likely to have gender parity on their boards compared to the 170 organisations that we understand to have boards, but do not have policies (or do not have them publicly available).

30 organisations in our sample have fewer than 3 women on their governing bodies-despite significant evidence suggesting that it takes a critical mass of at least 3 women to fully reap the benefits of gender diversity.

At the level of the board do organisations have policies to promote diversity and inclusion?

We found four sectors where not a single organisation had a board diversity policy in place.

Key takeaways from our findings

Gender and geography of global health leadership

Gender parity in senior management and governing bodies

Inching towards gender parity in global organisations

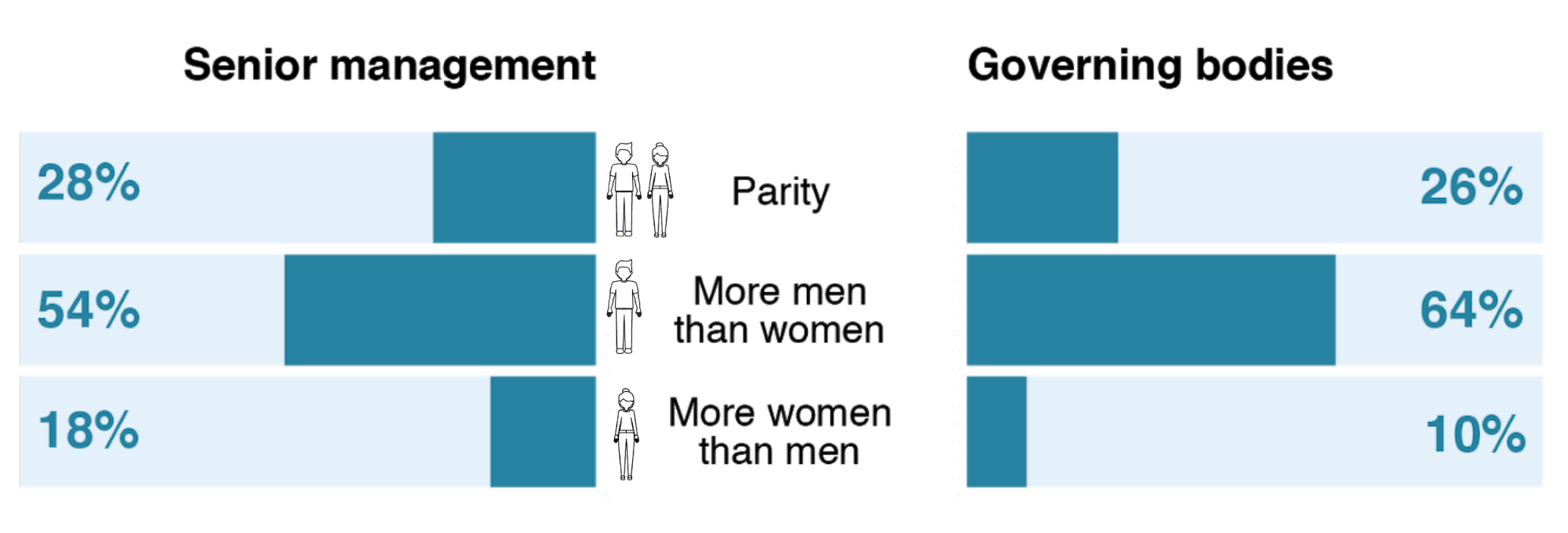

The number of women and men in positions of authority provides a strong measure of equity in career advancement, decision-making and power.

In many ways, the professional world operates at the end of a long pipeline littered with obstacles for many people. But organisations can decide whether to passively reinforce or actively correct historical disadvantage and inequality.

Findings

Decision-making bodies are still disproportionately male

We see indications of progress towards equal representation of women and men in decision-making bodies, albeit slowly. Among the organisations reviewed since 2018, the number of organisations with at least one-third women in these positions has grown from 56% to 65%. Eleven (11) organisations increased the representation of women in senior management from less than one-third (Red) to 35-44% (Amber). While parity (Green) figures haven’t moved substantially, organisations are moving in the right direction.

The proportion of governing bodies with at least ⅓ women has grown from 47% to 51%.

Will we wait for parity until 2074?

At the current rate of change, it will take:

54 years to reach gender parity in senior management and 37 years on governing bodies.

Can we shave a few decades off of that forecast?

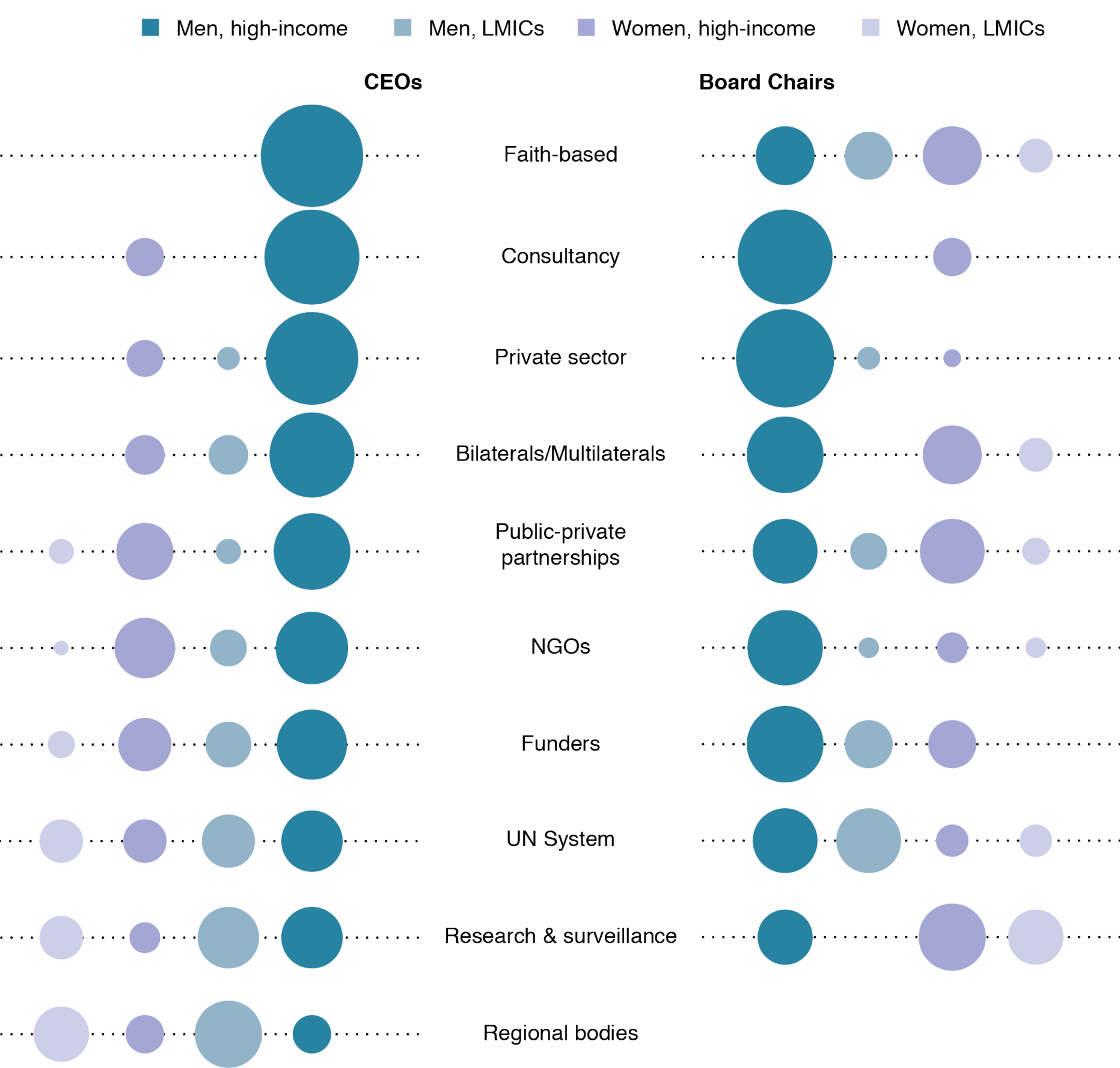

Gender of CEOs and board chairs

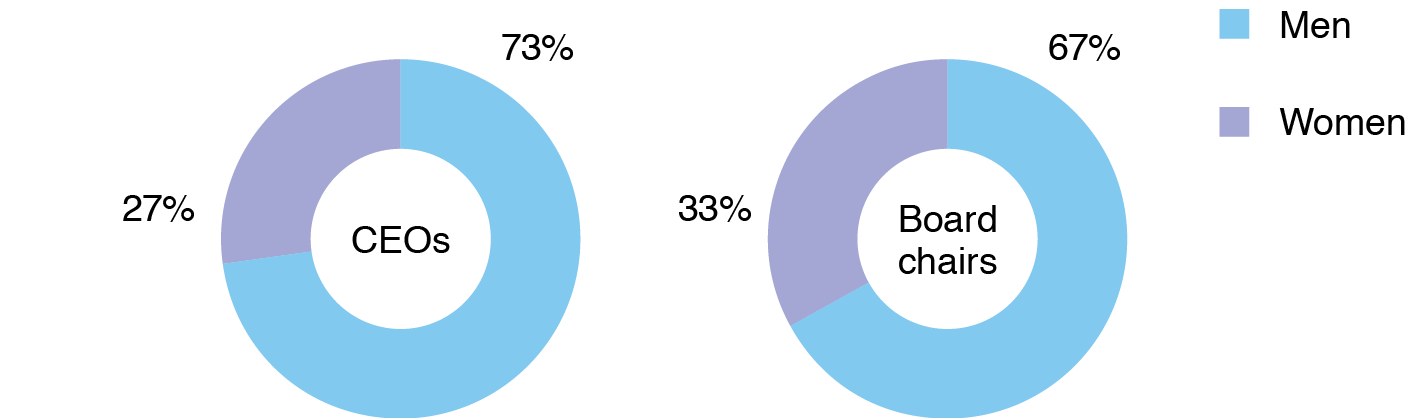

Parity at the top? Not anytime soon.

Findings

Despite the recent wave in media and public attention to clearing the path for women’s ascent in the workplace, the number of women reaching the top (executive) has barely budged.

CEOs and Board Chairs are still predominantly male

Gender of CEOs and Board Chairs

From 2018 to 2020, the total number of female CEOs increased by 1 (from 41 to 42 out of 139 CEOs total).

This isn’t merely a result of slow turnover at the top. On average, one in five organisations under review welcome a new CEO each year. In 2019, 64% of these new CEOs were male. Simply, men continue to be succeeded by other men.

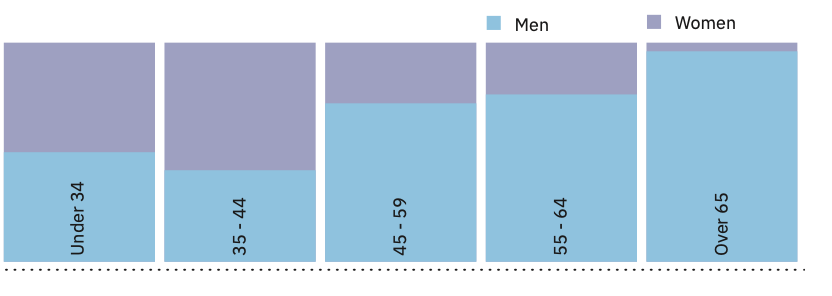

There may be an indication that progress towards parity is on the horizon: among CEOs under the age of 44 (of which there are only 16), women and men are more equally represented. Whether this is a sign of generational progress, or will turn out to be another example of female attrition along the career pathway, remains to be seen. This finding reinforces growing evidence that the gender pay gap is an age issue. Even in contexts where the gender pay gap is close to zero at early professional stages, gaps widen substantially later in life.

How does the distribution of women in leadership vary by age?

Trends are slightly more encouraging among board chairs. Faster progress is due to more rapid turnover in board chairs: 30% of organisations saw new chairs in 2019.

67% of board chairs are men. Among the organisations reviewed three years in a row, seven outgoing male board chairs were succeeded by women, increasing the percentage of women board chairs from 20% in 2018 to 26% in 2020.

Read more about the gender breakdown of CEOs and board chair by sector here.

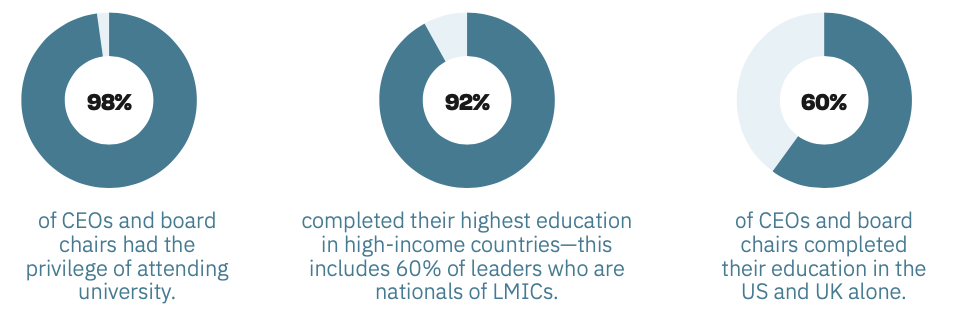

Demographics of CEOs and board chairs

Power in global health remains firmly in the grasp of the Global North

GH5050 gathered publicly available demographic information in addition to gender on the CEOs and board chairs of the 200 organisations in our sample. This information included: nationality, highest educational degree attained, university where that degree was attained and approximate age. These proxy measures provide insights into who runs global health.

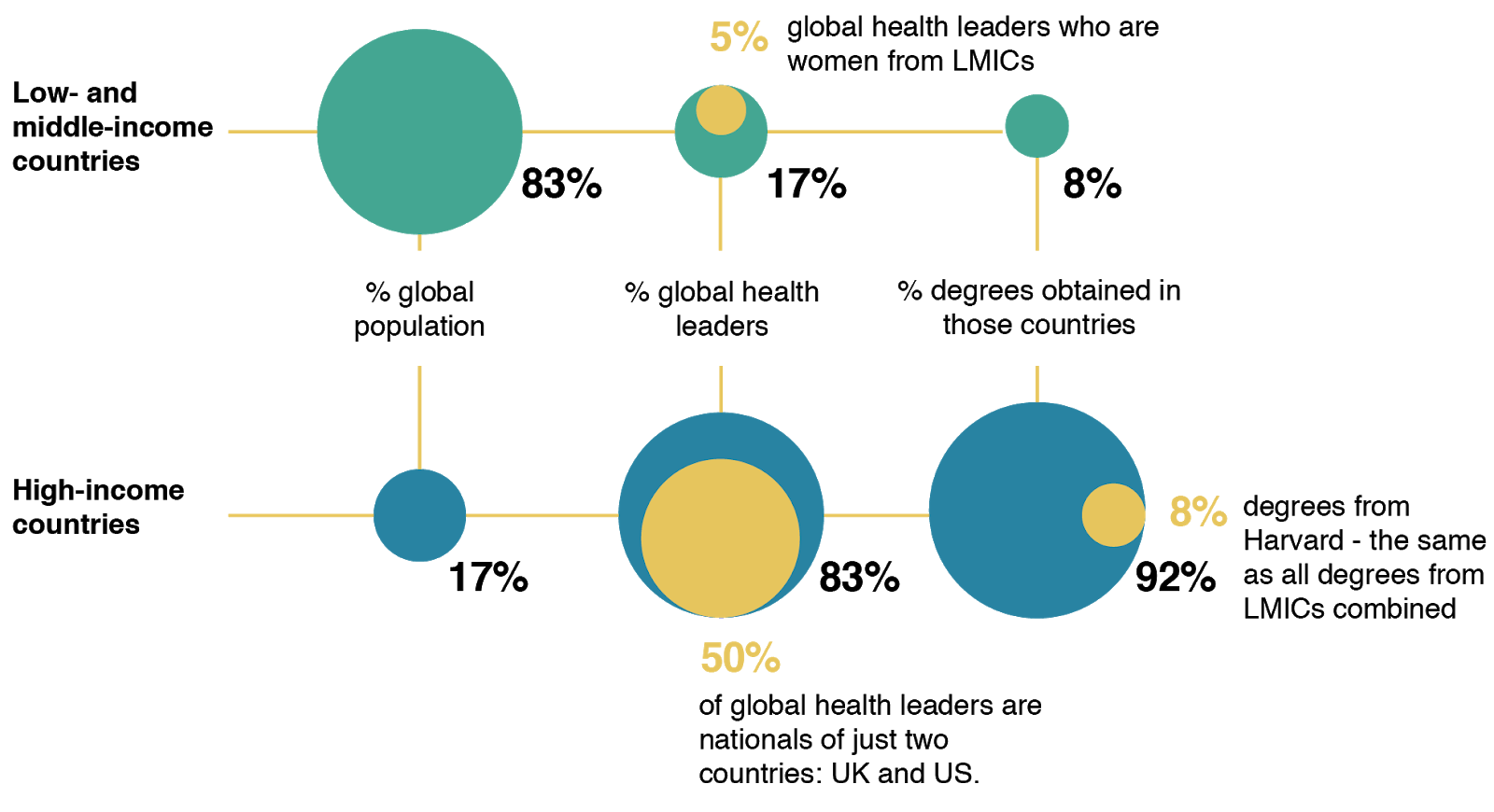

Findings: Privilege and nationality

17% of CEOs and board chairs are nationals of low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). These same countries are home to 83% of the global population. An additional six CEOs are dual nationals of a high-income country (HIC) and an LMIC.

Geography of global health leadership

How do power, privilege and education intersect?

Nationality of CEOs and Board Chairs by income level

Key takeaways from our findings

Do global organisations address the gendered Power dynamics of inequalities in health outcomes?

Gender-responsiveness of global health programmes

Strategies to advance health veer from gender-blind to gender-transformative in our sample

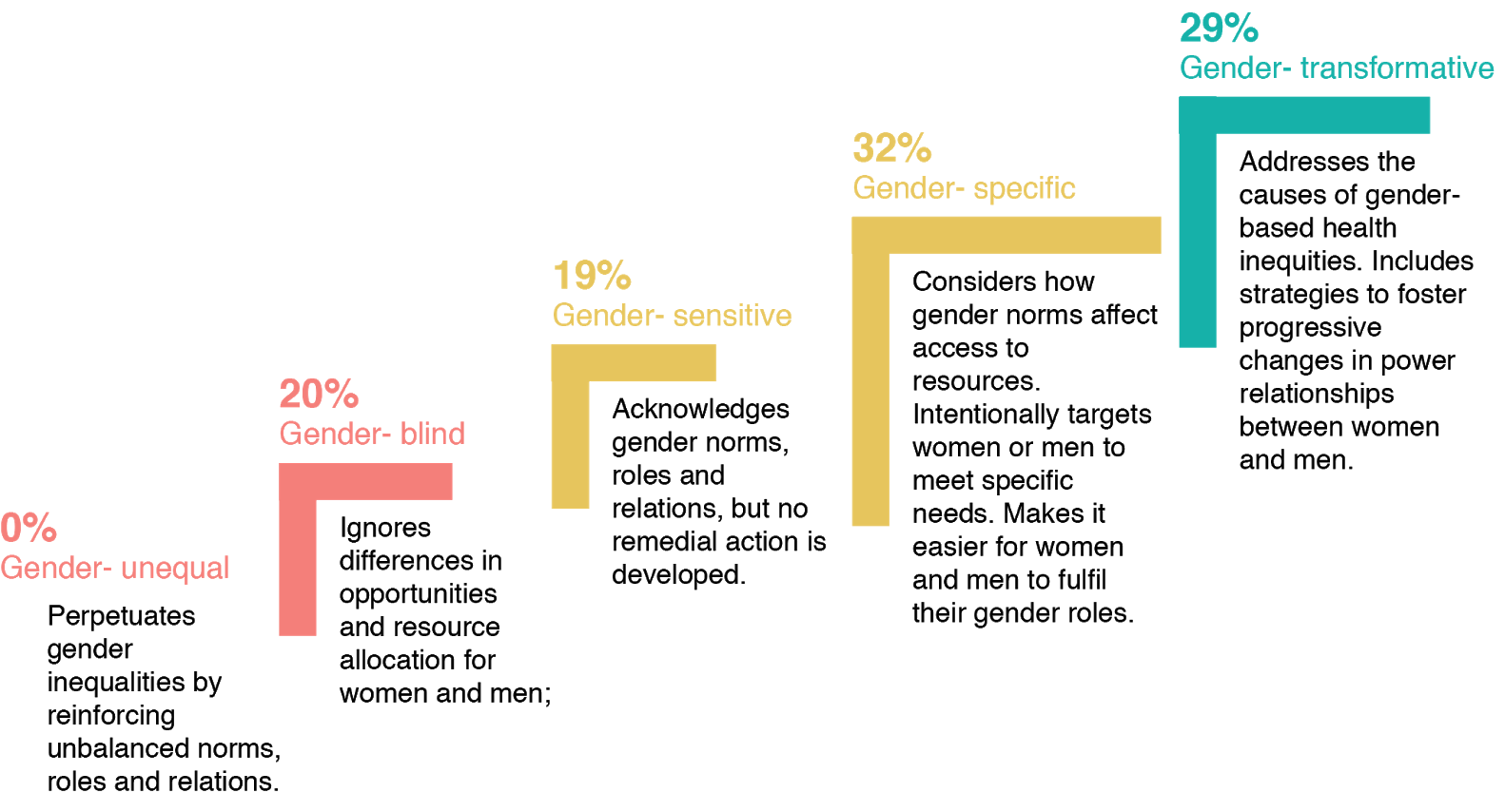

Much of the global health sector agrees that gender norms play a crucial role in perpetuating disparities in the distribution of the burden of ill-health across and within populations, and gender influences how organisations address the problem(s). We would therefore expect that their policies and programmes are fully gender-responsive. We find, however, a broad range in the gender-responsiveness of strategies, from those that address the underlying structural drivers of gender inequality, to those that ignore gender altogether.

Findings

Some organisations in our sample are among the global pioneers in analysing, understanding and working to transform the power dynamics and structures that reinforce gender-related inequalities in health outcomes. A total of 29% of organisations promote transformative strategies to address the systemic inequalities underlying the gendered distribution of power and privilege in health programmes. Around two-fifths of these organisations focus on women and girls as the primary beneficiaries, while the majority address gender norms in both girls and women and boys and men.

20% of organisations reviewed were entirely gender-blind, but no organisations were gender unequal.

Of the 158 total organisations (80%) with strategies found to be gender-responsive, 95 were primarily focused on meeting the needs of women and girls. None focused on primarily meeting the health needs of men. Sixty-three are gender-responsive to meet the needs of both women and men. Only 12 specifically mention the health needs of transgender populations.

Gender-responsiveness of organisational approaches (applying the WHO Gender-Responsiveness Scale)

See the WHO Scale.

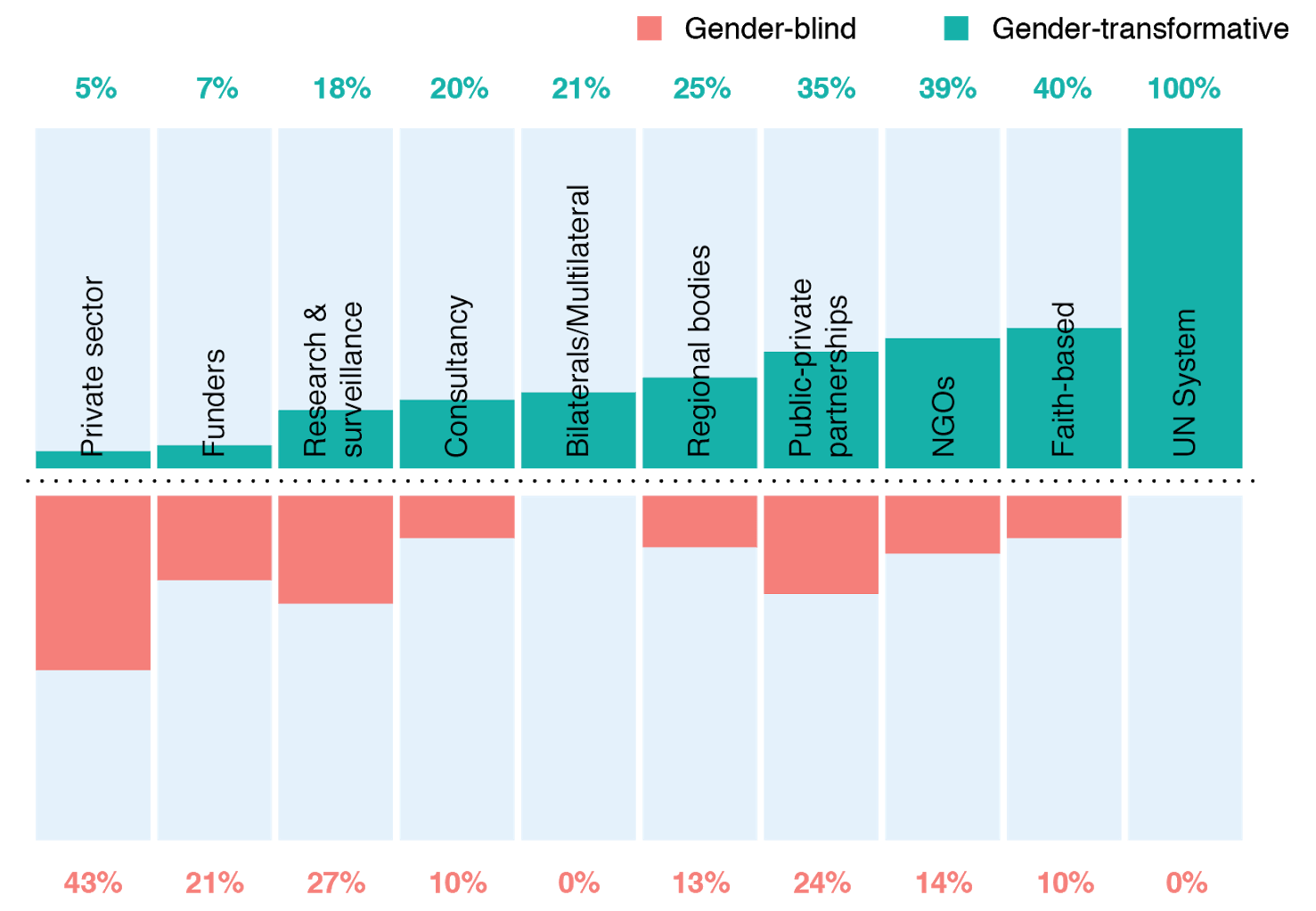

Organisational approaches to address underlying gender-related drivers of ill-health, by sector

Sex-disaggregated monitoring and evaluation data

The power of data

In assessing this variable in previous reports, GH5050 deemed the sex-disaggregation of a single data point to be sufficient for an organisation to score positively. This year, we have raised the bar and instead require organisations to show consistent sex-disaggregation of data across core reports, policies and/or strategies in order to score positively.

Findings

Fewer than four out of ten organisations commit to and fully sex-disaggregate data on programmatic delivery.

This includes roughly half of research and surveillance bodies, one-third of NGOs and one-fifth of private funders. No faith-based organisations in our sample disaggregate their M&E data by sex.

Do organisations sex-disaggregate their monitoring and evaluation data?

Of those that do, how do different sectors perform?

Takeaways from our findings

The global health agenda: Which priorities and for whom?

Are global health organisations aligned with the health agenda established by the SDGs?

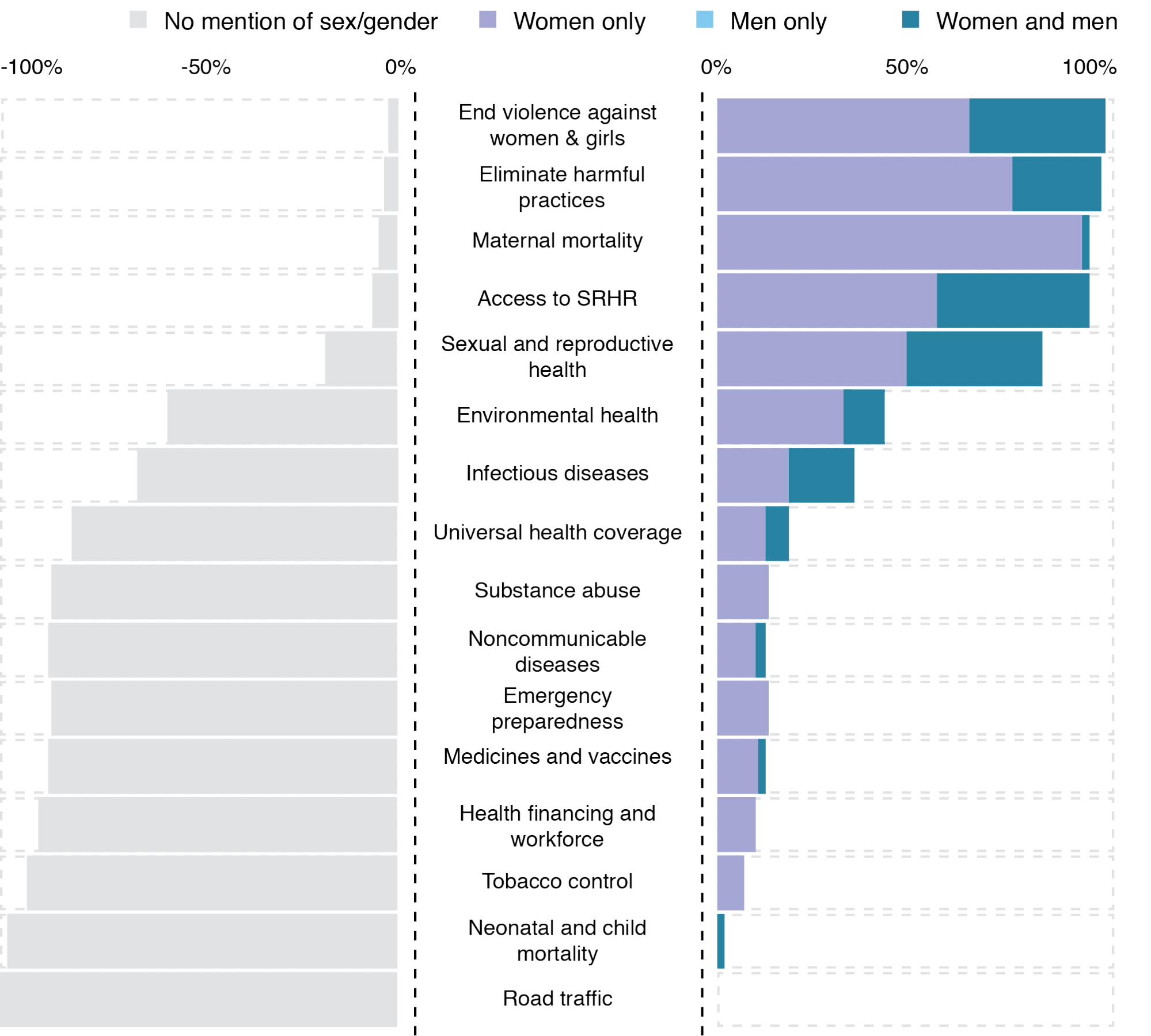

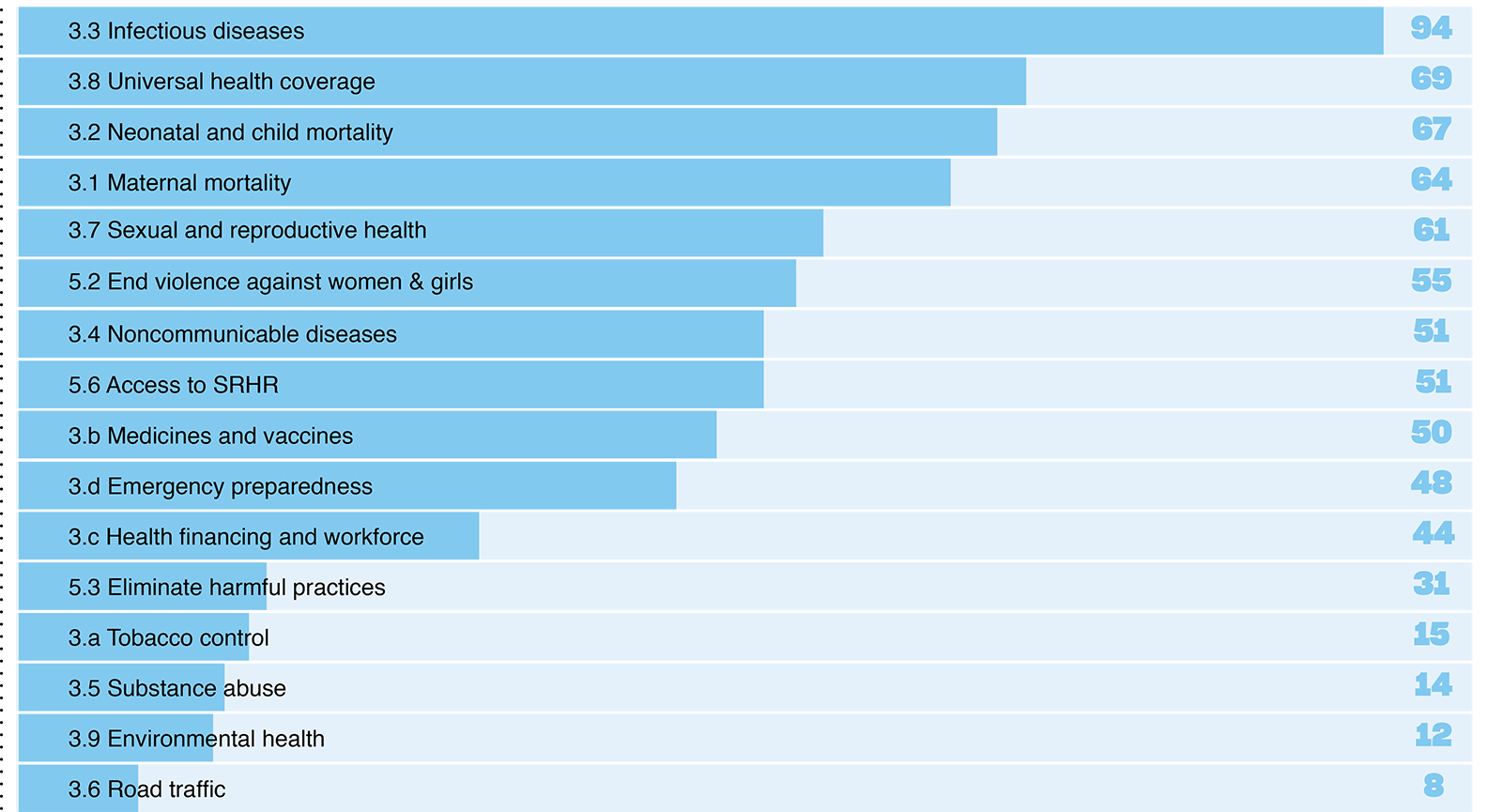

To explore the extent to which global health organisations are working across the SDG health agenda, GH5050 reviewed the mission statements and core strategies of 146 organisations in our 2020 sample. We identified organisations’ stated priorities and assessed how they align to the targets of SDG 3 and three targets of SDG 5 (“the gender equality goal”). These latter targets were: 5.2 (elimination of all violence against women and girls); 5.3 (elimination of harmful practices such as child marriage); and 5.6 (universal access to sexual and reproductive health and reproductive rights).

We did not include the 42 private sector companies nor the 10 consultancy companies in this sub-analysis. Many of the private sector companies generally seek to influence global health policy, but do not have global health promotion or action to advance the health-related SDGs as a core function. This means that identification of their priorities in line with SDG targets is difficult to assess from their websites.

Number of organisations (146 in total) that state a focus on each SDG 3 target and health-related SDG 5 target.

What is the burden of disease associated with the SDG health-related targets?

We find that not all health-related SDG targets receive the same amount of attention from global health organisations-ranging from 94 organisations that prioritised work on target 3.3 (infectious diseases) to 8 that prioritised work on target 3.6 (road traffic injuries and deaths).

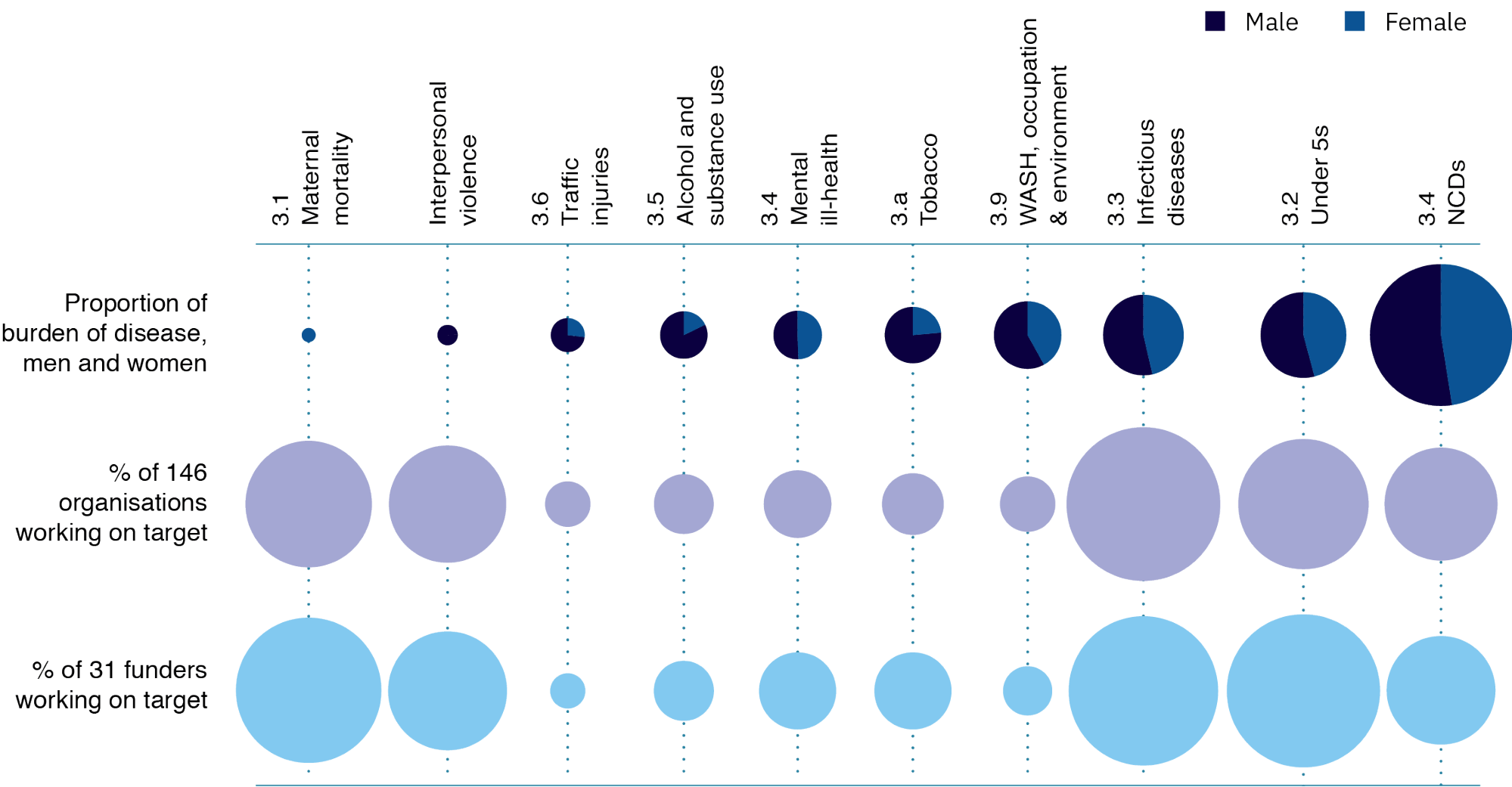

One explanation for this could be that some targets represent areas that have a lower burden of disease in the global population. We therefore calculated the burden of disease associated with each target in order to compare to the number of organisations focusing on each target.

Are organisational priorities aligned with the distribution of the burden of disease?

The following figure compares the burden of disease and organisational priorities. It presents the organisational focus of two groups: the overall sample of 146 organisations, and a subset of 31 organisations that are classified as exerting financial power.

We found a mismatch between attention paid by organisations (all, and financing subset) to some targets and global burdens of disease associated with those targets. Of note, those health issues that represent a continuation of the MDG agenda- maternal and child mortality and infectious diseases-continue to receive the largest proportion of attention of the global health ecosystem. The newer SDG-era targets, particularly NCDs, do not receive proportional attention from funders or other organisations.

Assessing alignment: global burden of disease compared to organisational priorities

Health issues that represent a continuation of the MDG agenda continue to receive the most attention of the global health system. Newer SDG-era targets, particularly NCDs, do not receive proportional attention.

Which populations do global health organisations target?

Given the differences in the distribution of DALYs between men and women, we also assessed whether organisations mentioned targeting specific populations-i.e. women and girls, men and boys, both or neither-in relation to their programmatic priorities. We found 72 organisations focused on one sex only. We did not find any organisation working solely on men’s health; all organisations with a single-sex/gender focus were concerned with advancing the health of women and girls. The other 74 organisations were either focused on the whole population or did not specify who they were targeting. For the sex-specific SDG targets (3.1, 5.2 and 5.3, i.e. reducing maternal mortality, and eliminating violence and harmful practices suffered by women and girls), a focus on women and girls would seem to be consistent with the aims of the targets. For other targets, however, the rationale for a sex-specific focus is less clear.

A sex-specific focus is not synonymous with being fully gender-responsive. We find that the majority of organisations are not gender- transformative in their policies and programmes. This is despite the role that gender plays in driving risk exposure and health outcomes across all targets.

Organisations that specify a population focus in their programmatic priorities, by SDG target