Narrowing the gender pay gap – minimal progress among UK-based organisations working in global health

Median gender pay gap shows minimal decrease among the 40 UK-based organisations reviewed by Global Health 50/50 in 2018 and 2019.

By law, organisations in the UK with 250 employees or more must submit their gender pay gap data to the Government of the United Kingdom and publish their results on their own public-facing website. The hope is that greater transparency will spur collective action to close the gap. As the deadline for reporting data for the 2018/19 figures recently passed, we wanted to check in and see if there had been any change in the figures of the UK-based organisations included in the Global Health 50/50 2019 sample. But before we get to the data, let’s be clear about what the gender pay gap measures.

The gender pay gap is the difference in the average hourly wage of all women and men in an organisation or across a workforce, as monitored by the Sustainable Development Goal indicator 8.5.1. Employees include those on part-time contracts and some self-employed people. In general, if men hold more of the better-paid posts than women, the gender pay gap is usually bigger. In the UK, employers are required to report not only on gender pay gaps, but also on the proportion of men and women in each pay quartile.

The gender pay gap represents the spread of men and women across the levels of an organisation. This is not the same as unequal pay, which is paying men and women differently for performing the same (or similar) work. Unequal pay is prohibited in some 64 countries, which include the headquarters location of nearly 90% of the Global Health 50/50 2019 sample of organisations.

The Global Health 50/50 2019 Report, Equality Works, reviewed the gender pay gap data reported by 41 of the organisations in our sample for the 2017/18 reporting cycle. Forty organisations also reported for the 2018/19 cycle (General Electric did not report for 2018/19). For this reason, we decided to rerun our 2017/18 analysis with the 40 organisations reporting for both cycles.

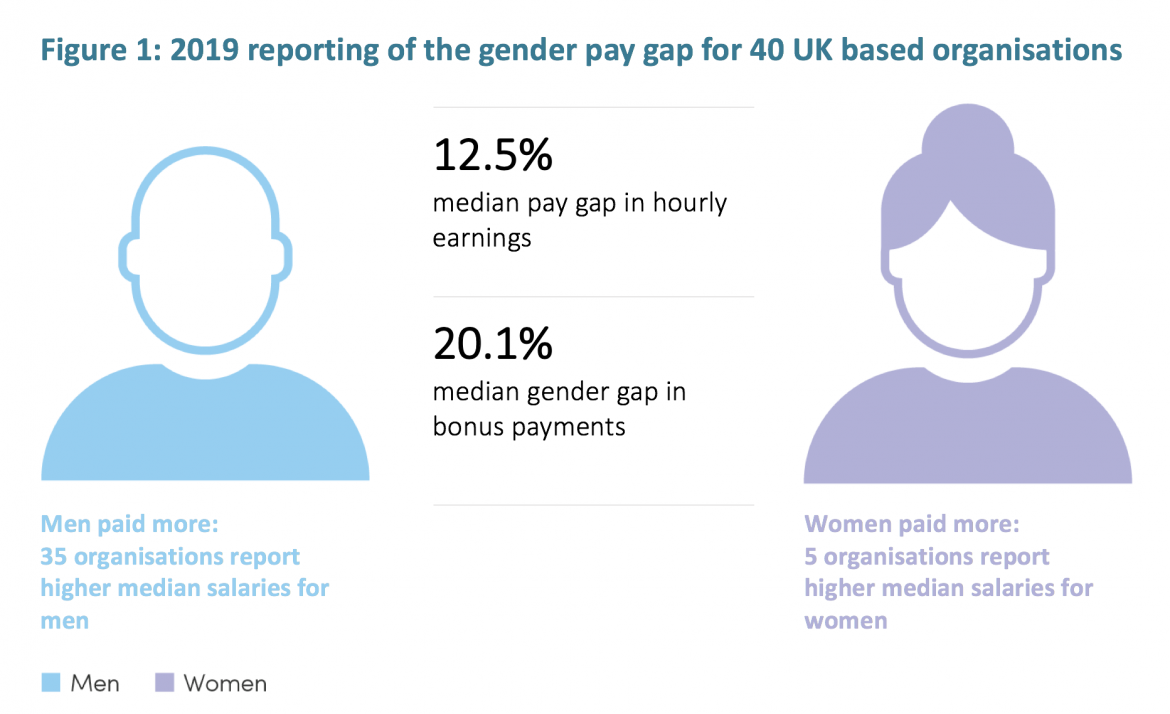

In 2017/18 the median (middle value) salary for women was 12.9% lower than the median salary for men – and this figure dropped slightly to 12.5% in 2018/19. With only five organisations reporting a median pay gap in favour of women, the size of the gap ranged from -39% in favour of women to 39.4% in favour of men.

A large proportion of employees in the 40 organisations receive bonus pay – well over 80% of both men and women, in both rounds of reporting. However, while the number of organisations reporting higher bonuses for women than men doubled to 8, the overall gender gap in median bonus pay across all 40 organisations remains at over 20% – see Figure 1.

It has been widely reported that a number of businesses and organisations have reported an increase in their gender pay gap figures for the 2018/19 reporting cycle. While shining a spotlight on these gaps is an important tool to spur action, these results affirm that there are no quick fixes.

We congratulate the UK government for mandating reporting on the gender pay gap. In the absence of statutory requirements, organisations rarely publish their remuneration disaggregated by gender. For example, only 8 organisations from outside the UK reviewed by GH5050 in 2019 report their gender pay gap, and across some sectors no organisations reported their gender pay gap figures (for example, the UN). We believe that transparency is the first rule of accountability, and we urge organisations to make a commitment to calculate and openly report on their gender pay gap data in the coming year.

In order to address the full range of structural inequalities which limit the potential, pay and power of our workforces, it is essential too that in the UK and worldwide we push for transparency and action across the many diverse drivers of inequities. Gender is just one of these. Applying an intersectional lens, a term coined by scholar and civil rights advocate Kimberlé Crenshaw, helps us to understand how multiple forms of discrimination can occur simultaneously. To reveal the intersectional reality of the pay gap, organisations should disaggregate the gender pay gap by other identifiable characteristics relevant to the context such as race/ethnicity or disability status, to analyse whether specific groups may be facing multiple disadvantages.

Simply reporting the data is a necessary first step, but follow-up action is then required to close the gender pay and bonus gaps found across organisations active in global health. For a full list of our recommendations on steps your organisation can take to close the gender pay gap, see page 84 of the Equality Works report. If your organisation is interested in learning how to calculate its gender pay gap, these resources provide a step-by-step guide as well as practical guidance on how your organisation can close its gender pay gap.

Charlotte Brown

Communications at Global Health 50/50