The gender pay gap provides a stark measure of power and privilege by comparing the average hourly pay of men and women. Typically, the gap reflects the gendered distribution of employees across the levels of an organisation—if an organisation has more men in senior positions and more women in lower-paid posts, it will have a wider gender pay gap.

A gender pay gap report is not the same as an equal pay audit—the latter is designed to capture any (often illegal) instances of paying men and women differently for the same work.

Following a year of unprecedented disruption to working lives, major increases in the burden of unpaid care, and evidence from countries around the world that women have suffered job loss, financial hardship and increased poverty at higher rates than men, measuring the gender pay gap takes on a new level of urgency.

Findings

One-quarter of the sample (51 organisations) publicly report gender pay gap data on their workforce. Among these, 45 organisations are required under national law to submit gender pay gap reports, including 44 under UK law and one under French law. There was little increase in the proportion of organisations reporting their gender pay gap in 2021 (27%) compared to 2019 (25%). An additional two organisations informed GH5050 that they regularly conduct gender pay gap analyses and make adjustments in light of findings, but do not publish the results.

Six organisations voluntarily calculate and publish their gender pay gap data in the absence of statutory requirements: Care International, EngenderHealth, IPPF, International Rescue Committee, Medicines for Malaria Venture and Palladium Group.

An additional 15 organisations informed GH5050 that they have recently conducted an equal pay audit to identify whether women and men are being paid differently for comparable jobs.

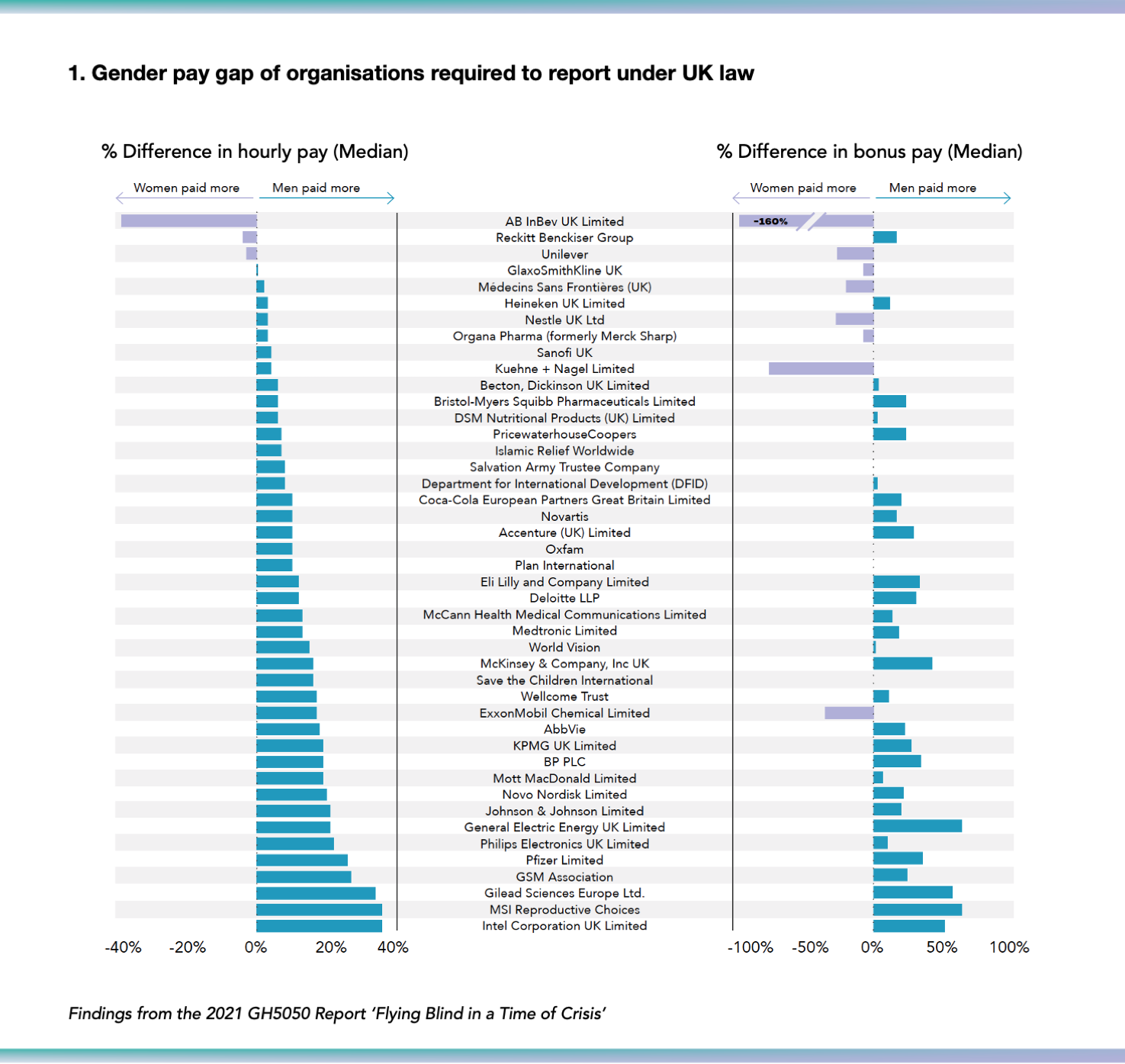

Given that the vast majority of available gender pay gap data is published by UK-based organisations, our analysis focuses on this data. Data in this report is drawn from a snapshot of income information from 2018 and 2019, which is the latest available from the official UK Government website.

Among the 44 organisations required to report under UK law,1 the gender pay gap ranged from -39% (in favour of women) to +36% (in favour of men), and on average, a median pay gap of 11.2%. In other words, across organisations reporting, all male employees capture on average 11.2% more salary than all women employees.

Among the 39 organisations reviewed in 2019 and 2021, the median gender pay gap grew from 12.9% to 13.7%, in men’s favour.

In 39 of the 44 (87%) organisations, median pay for men is higher than for women. Median pay is higher for women than men in three organisations (AB inBev, Reckitt Benckiser, Unilever), and roughly the same in two organisations (+/-2%; GlaxoSmithKlein, Medecins Sans Frontieres). Full details can be found here.

Among the 39 UK organisations for which data was available in 2019 (2017 data) and 2021 (2019 and 2018 data), the median gender pay gap grew from 12.9% to 13.7%, in men’s favour. The median proportion of women in the top quartile increased slightly, from 36% to 39%.

Nice, but not necessary: UK requirement to report gender pay gap reporting suspended during COVID-19

Enforcement of gender pay gap reporting requirements in the UK was suspended on 24 March 2020, 6 days before the reporting deadline for public organisations, and 10 days before private companies were required to report their annual figures. The Government Equalities Office defended the decision as a reprieve for HR departments tasked with keeping employees and their businesses safe in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Many however criticised the decision, particularly in light of the high number of women who had already been furloughed or worked reduced hours due to caring responsibilities by that time. Proponents of continued gender pay gap reporting argued that evidence of reversals of progress towards gender equality should have been met with more rather than less transparency.

Among our sample of 52 UK-based organisations required to report under normal circumstances, seven opted out last year.

At the time of writing, it appears that the requirement of private businesses to report on their pay gap in early April 2021 will be reinstated.

Source: https://www.fawcettsociety.org.uk/news/fawcett-leads-calls-to-reinstate-gender-pay-gap-reporting

EngenderHealth calculates and reports its gender pay gap among global staff as well as in country offices as part of its commitment to advance diversity, equity and inclusion across the entire organisation.

Inequity at the top: within-band inequity among CEOs

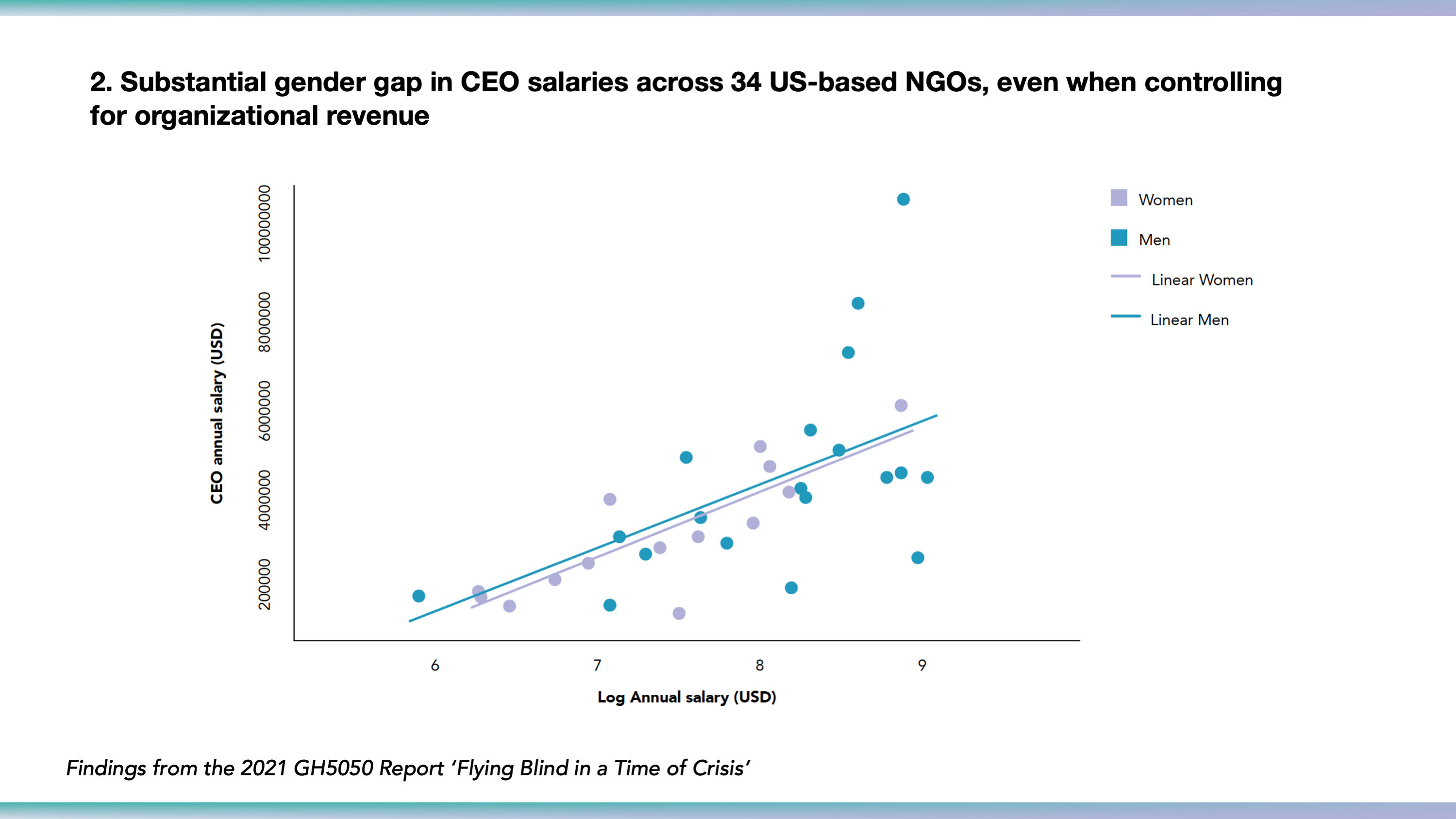

To provide a snapshot of whether the gender of the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) is associated with rates of pay, Global Health 50/50 gathered publicly available financial reporting (from the US Internal Revenue Service) for the non-governmental organisations (NGOs) based in the USA and included in our sample. Financial data were available for a total of 34 NGOs, 20 of which are led by men and 14 by women.

Rates of pay ranged between $150,000 and $965,000 per annum. Salaries were consistently higher for male CEOs, on average by $106,000 per year, compared to female CEOs across all sizes of organisation (which ranged from $600,000 to over $1 billion in annual revenue). Additionally, the average total revenue of organisations led by men was over three times that of organisations led by women.

Even when controlling for organisations’ revenue, a substantial gap of $45,000 between male and female CEOs’ salaries remain. This is larger than GH5050’s findings in 2019 when the calculated gap was $41,000.

$45,000 gap:

Women CEOs are annually paid $45,000 less than men CEOs, on average and when controlling for organisations’ revenue.

Organisations of all pay structures and sizes should calculate their gender pay gap

Many organisations determine pay levels based on a predetermined pay scale. While such a scale makes within-band pay inequalities unlikely, organisations with set pay scales may still have large gender pay gaps if women and men are unequally represented at different pay bands.

Conducting a gender pay gap for such organisations, such as United Nations agencies, and for all workers, including those working part-time and consultants, should be considered an essential monitoring tool to unearth inequalities across the entire workforce.

An intersectional approach to reporting the pay gap

Inequities in pay outcomes operate not only to disadvantage women, but also other people in the workplace. Some organisations in our sample are leading the way in commitments to fair and equitable pay by going beyond gender to monitor and report pay gaps between other demographics of the workforce, including by characteristics such as ethnicity, race and ability.

“Wellcome’s ethnicity pay gap calculates average rates paid to all our employees from black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) backgrounds compared with average rates paid to all our employees from white (non-BAME) backgrounds. [...] At Wellcome, we see our ethnicity pay gap as one important measure of how much more we have to do to become an inclusive place to work.”

Wellcome Trust, Ethnicity pay gap reporting 2019

Access the data

See details of the gender pay gap among organisations reporting here: https://globalhealth5050.org/2021-detailed-findings/

1 UK-based organisations are required to report data using a standardised methodology for the following variables: (1) mean and median pay gap in hourly wages of men and women; (2) mean and median bonus pay gap among men and women; (3) proportion of men and women occupying pay quartiles; and (4) percentage of men and women receiving bonuses. UK guidelines include both employed workers and some self-employed people in the calculations.