The role of sex and gender in the COVID-19 pandemic

COVID-19 is a gendered pandemic. From issues of livelihoods to child care, gender-based violence to food security, there are differences - socially, politically, economically - in how people of different genders are experiencing and being impacted by the virus and responses to it.

Health outcomes related to COVID-19 are similarly affected by gender and sex. Biological sex (which influences hormonal, immunological and physiological systems in the body) and gender (socially constructed and influencing roles, norms, expectations, power and position for all people in society) both play an important role in how individuals and communities experience the pandemic.

Data from the GH5050 COVID-19 Sex-disaggregated Data Tracker, which collates sex-disaggregated evidence from national surveillance reports from 190+ countries, shows differences between men and women in COVID-19 health outcomes across the exposure-to-outcome pathway. Globally, men are less likely to be tested for COVID-19, more likely to be hospitalised, and more likely to die from the virus, compared to women. Data for transgender and non-binary people are generally absent from national surveillance data.

Globally, men are less likely to be tested for COVID-19, more likely to be hospitalised, and more likely to die from the virus, compared to women.

What explains these differences? In part, biology. Research suggests that different immune responses, linked to having XX or XY chromosomes in the body, may influence the likelihood of severe COVID-19 disease and death.1

But biology only tells a small part of the story: gender plays a role at all points in the COVID-19 pathway. Exposure to the virus and access to COVID-19 -related health services are affected by gender and influence COVID-19-related outcomes (see Box 1). Not all men and women experience the same environmental, social, economic and political factors that play a role in determining their health outcomes in relation to COVID-19. Inequalities related to race, class, caste, disability, sexuality and age intersect with sex and gender to create complex and overlapping vulnerabilities to the impact of COVID-19.

Box 1. Examples of how gender impacts COVID-19 health outcomes

| Exposure to COVID-19 | In some countries the high proportion of cases among men may result from gender norms around who participates in the paid labour market (meaning, for example, that women are less present in crowded factories or on public transport). In other settings, women face increased exposure to infection, particularly in countries where they make up the majority of frontline workers in health and social care. |

| Access to testing and health care | Access to services, including intensive care units, may be limited for people without the financial resources to pay for care, meaning women may have less access in some settings. However, even in countries where healthcare is universal and free, rates of hospitalisation are often higher in men. |

| Vulnerability due to pre-existing health conditions | The chronic diseases associated with more severe COVID-19 disease and higher death rates are frequently more common in men - and often associated with men’s higher rates of exposure to unhealthy behavior and environments over their lifetimes (such as tobacco use, exposure to air pollution, and poor diets). |

| Gendered data gaps | In highly gender unequal countries, gender gaps in reported mortality rates may to some extent reflect the failure to register women’s deaths within vital registration systems. |

“The focus should be on gathering more evidence for targeted decision making. The [GH5050] report is a great starting point for that. Organisations can no longer avoid gender in their responses if we want to achieve an equitable recovery to the pandemic.”

Sneha Sharma, Senior Research and Program Associate, International Center for Research on Women

Applying a gender lens to pandemic responses

Evidence from past pandemics suggests that taking gender and intersecting vulnerabilities into account when designing and delivering interventions to address COVID-19 will improve health outcomes for everyone. Conversely, pandemic response programmes without consideration of sex and gender can leave vulnerable and marginalised groups bearing a disproportionate burden of the pandemic and thereby exacerbate existing inequities.

WHO has recommended a number of public health interventions that every country should consider in pandemic responses, as well as essential support strategies from the international community (Box 2).2

Gender-responsive approaches to many of these areas can improve outcomes and ensure more equitable pandemic responses. This relies on inclusive policy design, implementation and accountability processes that meaningfully engage women, civil society and gender experts.3 4 Gender-responsive pandemic responses matter not only for immediate COVID-19 outcomes, but will contribute to building gender-responsive health systems and approaches.

Box 2. WHO-recommended pillars of national and international pandemic responses

| Core pillars of an effective national pandemic response | International support to countries’ response to COVID-19 |

|---|---|

|

|

A framework for examining organisations’ engagement in the health response to COVID-19

Global Health 50/50 conducted a review of 201 global organisations (2021 Report sample) active in health in order to understand their gendered response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

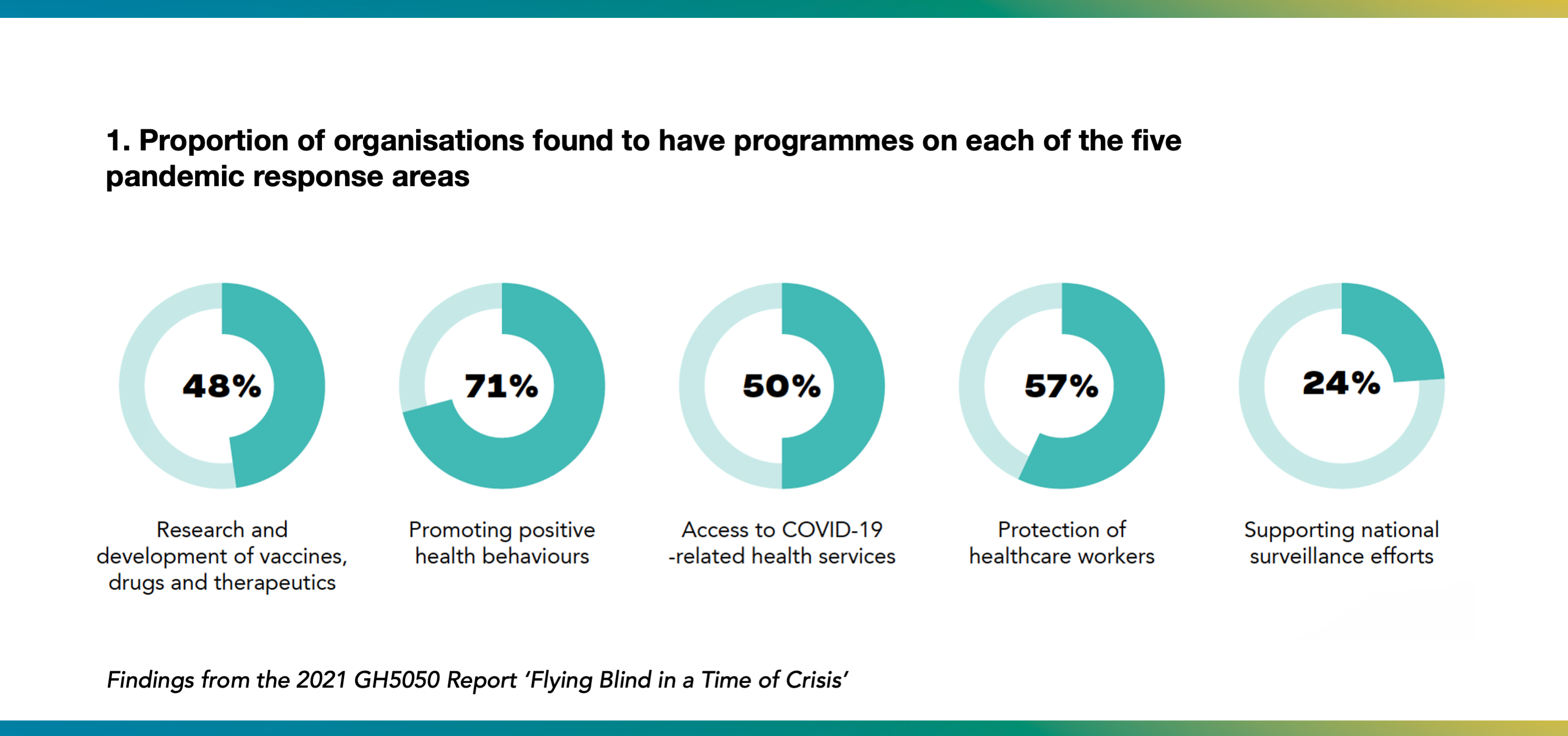

Five areas derived from WHO pandemic responses recommendations were reviewed:

- Research and development of vaccines, diagnostics and treatment.

- Encouraging positive health behaviours.

- Facilitating access to health services and systems.

- Ensuring the protection and care of healthcare workers.

- Supporting national and global COVID-19 surveillance.

The five areas were chosen as those: (i) that target the direct health impacts of the pandemic; (ii) where prior evidence suggests that using a gender-responsive design would improve outcomes; and (iii) which are relevant to the roles of global health organisations (not only national bodies).

Researchers reviewed each of the 201 organisations’ websites to answer three questions: (1) is the organisation working on any of these five areas? (2) how does the organisation’s COVID-19 work in these areas take sex and gender into account? and (3) which population is targeted (women, men, including transgender people, and non-binary people, or a combination)?

Using publicly available information from organisations’ websites, approaches to COVID-19 programming activities were assessed using the WHO gender-responsiveness assessment scale.5 See Methods for more on our methodology.

Do global health responses to COVID-19 take gender into account?

Among the 201 organisations, 70% (140) were found to have programmes focused on at least one of the five WHO-derived pandemic response areas (see Figure). A total of 349 activities addressing COVID-19 across these five areas were identified.

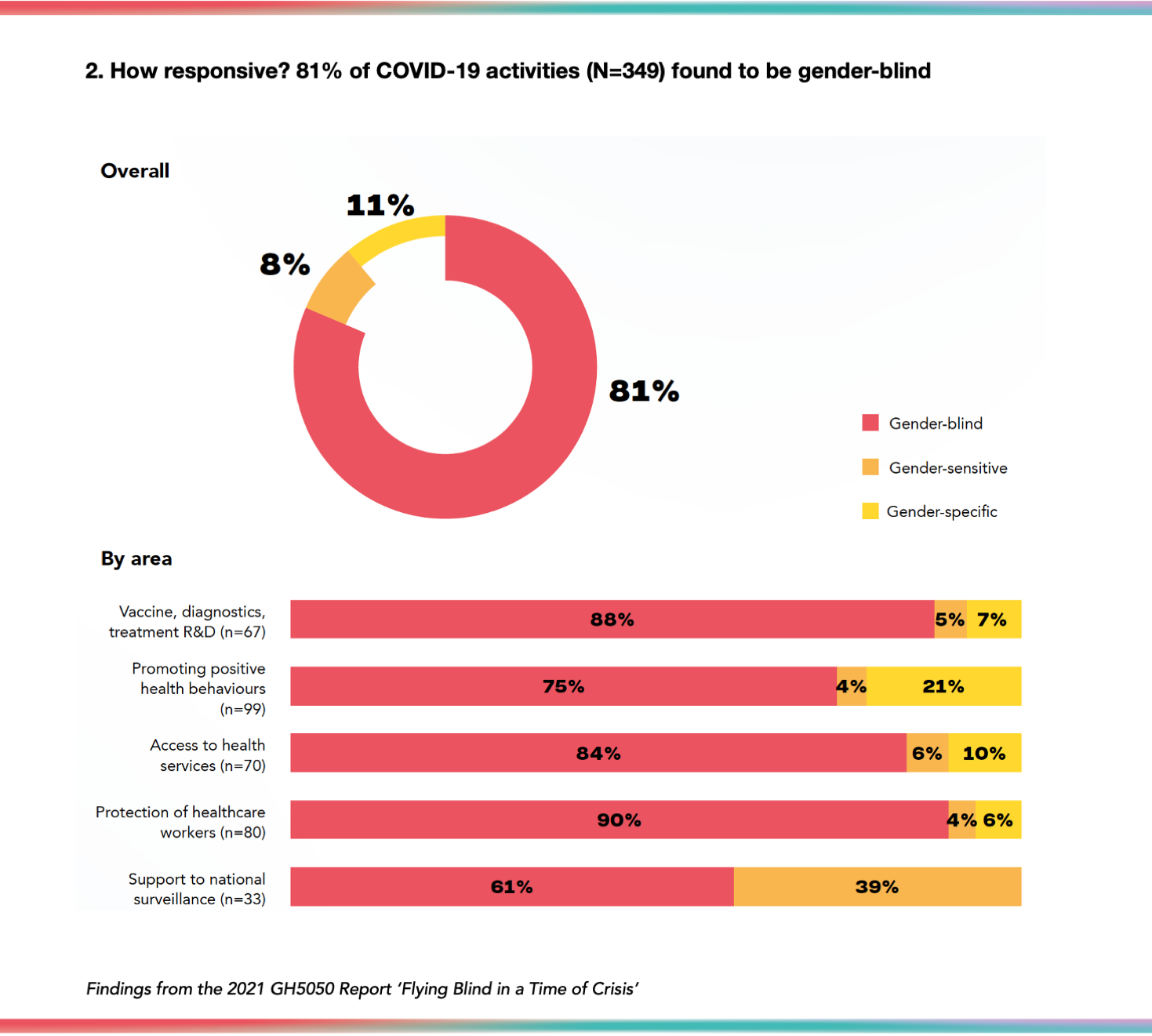

The majority of the 349 activities reviewed were found to be gender-blind - i.e. gender was not taken into account in the programme or policy reviewed - ranging from 60% to 90% across the five areas. Gender-blind approaches were seen most frequently in the following areas: 1) vaccine, therapy, and diagnostics R&D; 2) treatment of health services; and 3) protection of healthcare workers.

Just 8% (27/349) of COVID-19 activities were gender-sensitive, meaning that reference was made to the role of gender norms or inequalities in the pandemic, but no appropriate actions to address the impact of gender appeared to have been proposed or taken. 11% (38/349) of activities were gender-specific, meaning that activities were tailored to specifically reach men, women, transgender or non-binary people or a combination.

No activities were identified that were gender-transformative -- i.e. that address underlying causes of inequities and seek to foster progressive changes in gendered power relationships between people. This is in contrast to the analysis of the core, non-COVID-19 activities of the 201 organisations, which found that 39% organisations reported undertaking “gender-transformative” programming (Link).

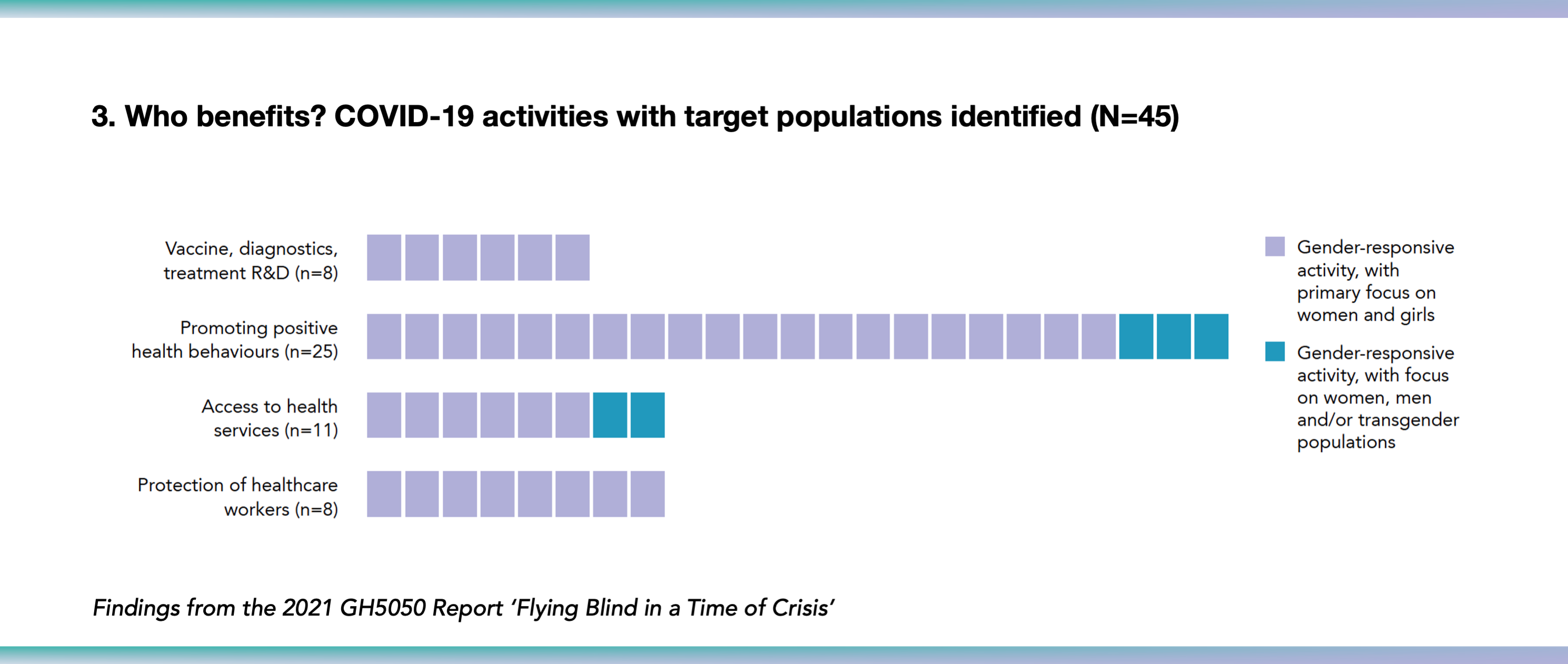

13% (45/349) of all recorded COVID-19 activities detailed which population(s) their gender-reponsive programmes were aiming to reach (i.e., men, women, trangender and non-binary people or a combination). The majority of these activities -- 88% (40/45 ) -- focused primarily on women and girls. Just five gender-responsive activities referenced the aim of reaching both men and women, including two that also acknowledged transgender populations.

Recommendations for gender-responsive pandemic responses

Many organisations in the sample provide only a high-level and brief overview of how they are contributing to responses to COVID-19. It may be too soon to expect detailed reporting on organisational activities, in what remains the height of the pandemic in many places. Some gender-responsive action is likely taking place around the world -- and ideally will come to light in future reporting. What this review suggests, however, is that for the vast majority of organisations, recognising the role of sex/gender in the pandemic or how it was being taken into account in programmatic activities did not appear to be sufficiently important to warrant reporting.

The few organisations that reported gender-responsive programmes focused almost exclusively on women, with few inclusive of men. This is concerning given that men are less likely to be tested for COVID-19, more likely to be hospitalised, and more likely to die as compared to women.

Comparing these findings with the stronger performance on gender-responsiveness of organisations’ core programmatic activities (Link) suggests that gender may have been deprioritised in this time of crisis.

GH5050 encourages organisations to integrate the following gender-responsive measures into their pandemic responses:

- Ensure that vaccine R&D accounts, at a minimum, for the role of sex in vaccine efficacy and the role of gender in rates of vaccine uptake. Monitor and evaluate the impact of sex and gender throughout vaccine roll-out.

- Apply a gender lens in the design and delivery of public health interventions to ensure equitable access to information on how to mitigate risk of infection and seek testing and treatment.

- Implement targeted measures to reach marginalised groups with testing, health services and registration systems to monitor the impact of COVID-19 on different populations to ensure equitable access to these services.

- Commit to understanding the needs of health and social care workers and guaranteeing equitable protection and support, including quality and properly-fitting PPE and appropriate mental health support.

- Carry out sex-disaggregated surveillance of and reporting on vaccinations, testing, cases, hospitalisations, ICU admissions, infections among healthcare workers, and deaths.

Taking a deeper look at five pandemic response areas:

Role of sex/gender, effectiveness of gender-responsive approaches, and illustrative examples from our review

This section presents evidence for the role that gender plays in each pandemic response area and select evidence of gender-responsive intervention effectiveness. Given the lack of current evidence from the COVID-19 pandemic, examples from gender-responsive approaches used in the control of other infectious diseases are included, including in pandemics and health emergencies. Illustrative examples are highlighted of gender-responsive work being done by organisations in the sample.

Research, development and delivery of vaccines, diagnostics and treatment

MAKING THE CASE

The issue

Sex (biology) and gender play a role in how people respond to vaccines and other pharmaceutical interventions through differences in immunological responses, drug metabolism and vaccine acceptability.

Evidence for the role that gender plays

Biological studies have shown that some vaccines may provoke a higher immune response in women compared to men.6 Conversely, some ‘acceptability’ studies in Europe,7 the UK8 and the US9 have indicated that women may be less likely than men to accept the COVID-19 vaccine. In the case of some drugs—including those used to treat influenza—men and women metabolise the drug differently,10 while other studies have shown that gender plays a role in both drug-prescribing11 and drug-compliance.12 Taking gender into account when designing trials is a key consideration.

Evidence for Interventions taking gender into account

Gender-specific HPV vaccine programmes that target both girls and boys have been shown to have a higher public health benefit, compared to those that target girls alone.13 A large community-based trial of HPV vaccine coverage in Finland, for example, found that high levels of coverage in young men also provided benefit to young women who had not been vaccinated—an important finding in comparison to the previously standard policy of only offering the vaccine to young women. Taking gender into account in this trial led to improved public health benefits for everyone.

OUR FINDINGS

Findings from our review

Sixty-seven organisations were found to be active in this area, for example in vaccine and drug research, developing diagnostics, monitoring vaccine efficacy and safety and funding countries to scale-up testing capacity. Among the 67 organisations, 12% (8/67) were found to be doing so with some level of gender-responsiveness, while 88% (59/67) were gender-blind.

Among the few gender-responsive interventions that were identified, their focus was primarily on researching COVID-19 in pregnant women and efforts to ensure gender-representation in vaccine and drug development. In all instances where the population targeted by the intervention was specified, the focus was on women.

Example of a gender-specific approach to COVID-19 vaccines, diagnostics and treatment R&D

“Abt is using an existing network of sites and protocols from CDC Pandemic Flu and Global Flu contracts to study COVID-19 in pregnant women. [...] We will identify COVID-19 (and vaccine) knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs, pregnancy/infant outcomes, and potential COVID-19 cases. The data can improve modelling of respiratory illness burden and characteristics during pregnancy.”14

Abt Associates, Emerging research into COVID-19 and pregnancy

Reducing exposure, promoting preventive behaviour, encouraging positive health behaviours

MAKING THE CASE

The issue

Risk of exposure to a virus, and response to that risk, including through adopting health-protective behaviours, varies according to the context of peoples’ lives. Capacity to respond to public health communications and interventions depends, among other things, on economic and social factors, trust in the State and public health services.

Evidence for the role that gender plays

In past respiratory pandemics and epidemics, women were generally more likely than men to adopt non-pharmaceutical behaviours such as hand washing, face mask use or avoiding public transport.15 Early evidence suggests that similar patterns are emerging in relation to COVID-19.16 A June 2020 survey across eight high-income countries found that women were 4.9% and 5.8% more likely to adopt recommended behaviours to reduce risk of infection in the first and second waves of the pandemic respectively.17 Some of these differences in behaviours are driven by gender. For example, men in paid employment that cannot be undertaken at home may not have the agency to avoid public transport to get to work and get paid.

Interventions that take gender into account

Experience from previous influenza pandemics,18 and from the HIV epidemic, have highlighted the importance of understanding and addressing the socio-economic context of people’s lives, and their perspectives on risk (and benefit) as lying at the heart of effective public health communications strategies.

Gender specific engagement measures in response to HIV, including comprehensive sexuality education for boys, peer education programmes and promoting social marketing of condoms have been effective at increasing health-seeking behaviours among men with low uptake of HIV testing services.19

OUR FINDINGS

Findings from our review

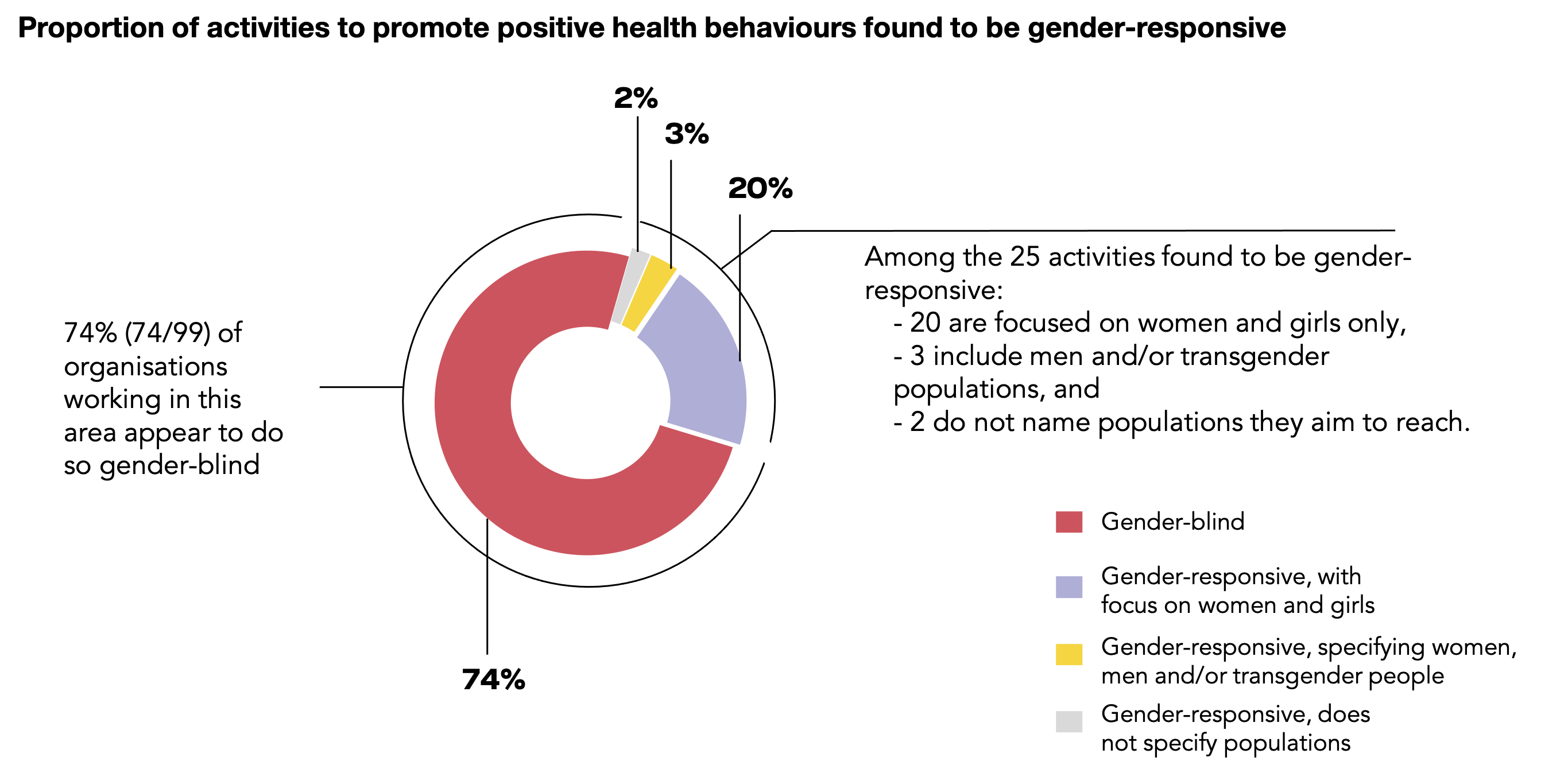

99 organisations reported working on promoting positive health behaviours and reducing exposure in the COVID-19 response. Interventions included awareness-raising campaigns on infection, risks and preventive behaviours as well as distribution of hygiene equipment.

Among these activities, 25% (25/99) were gender-responsive in some way while 75% (74/99) were gender-blind.

Gender-responsive activities included conducting sex-disaggregated studies into adherence to measures to reduce infection risk, training of women community health workers on infection-prevention, and COVID-19- awareness campaigns targeted towards women using health facilities. Among the 23 gender-responsive activities that mentioned which populations they aimed to reach, 20 focused on women and girls, and 3 included men and/or a specific focus on transgender populations in their target audience.

Example of a gender-sensitive approach to health promotion relating to COVID-19

“If you are investing in accelerating detection and suppression, keep in mind that there are gender-specific behavioral barriers to prevention and testing, and quarantine-induced increases in domestic care burdens and gender-based violence (GBV). Key [a]ctions [include] [i]ntegrat[ing] messaging and focused interventions to improve men’s health seeking behaviors (given their higher mortality from COVID-19) in COVID-19 testing efforts and education campaigns around personal and environmental hygiene.”20

Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Guidance for gender-responsive investments in the COVID response

Facilitating access to health services and systems

MAKING THE CASE

The issue

Differences in admissions to hospital, including to intensive care units, and deaths recorded in vital registration systems, may reflect the impact of gender on access to services and systems. “Access” captures a range of dimensions including: accessibility; availability; acceptability; affordability; and adequacy in service design, implementation and evaluation—all of which have gendered elements to them.21

Evidence for the role that gender plays

Heavy domestic, child-care and paid workload, the need for permission from male relatives to travel, and lack of access to transportation impact the accessibility of testing and treatment for women.22 Stigma around communicable diseases is also known to have deterred women from seeking testing, while lack of women’s financial autonomy can make services unaffordable.23 Societal notions of masculinity may delay care-seeking among men.24

Interventions that take gender into account

Studies have shown that the introduction of self-testing can be highly effective at increasing uptake among women and communities not traditionally reached by screening.25 This is because it can reduce stigma, be more convenient for those with work and family commitments, and reduce costs of travel to testing centres.

OUR FINDINGS

Findings from our review

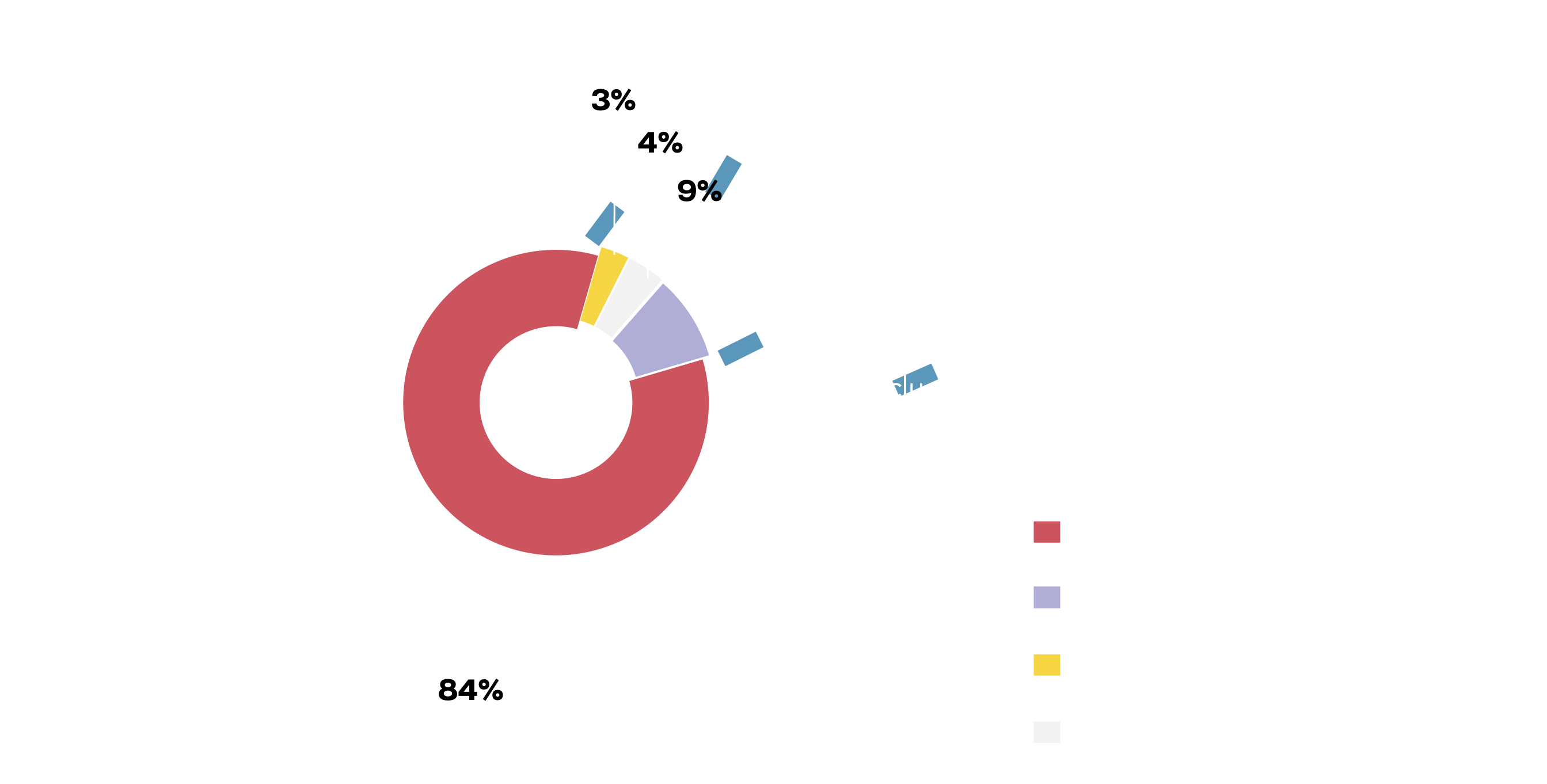

70 organisations reported working on facilitating access to health services for people with COVID-19. Activities in this area included efforts to prepare and build capacity of national healthcare systems, provision of medical devices and protective equipment, training for healthcare workers and support for countries with procurement of medical supplies.

Among these activities, 16% (11/70) were gender-responsive in some way while 84% (59/70) were gender-blind.

Gender-responsive activities included the establishment of mobile medical clinics to reach vulnerable women in remote areas or by acknowledging the different needs of men, women and gender diverse individuals in guidelines for national healthcare systems. Among the eight gender-responsive activities that mentioned which populations they aimed to reach, six focused on women and girls only, one referenced women and men, and one referenced women and men and specified transgender populations.

Example of a gender-specific approach to access to COVID-19 health services and systems

“Up to 60 percent of pregnancy-related deaths are preventable, highlighting inequities in health care access and quality-of-care factors that contribute to racial disparities in maternal mortality and severe morbidity. As such […] NIH has initiated large-scale studies to investigate the effects of COVID-19 on such factors as pre- and postnatal care, rate of Cesarean section delivery, and maternal health complications. […] NIH also will support research on the use of therapeutics to treat COVID-19 during pregnancy and breastfeeding”

National Institutes of Health, Investigating COVID-19 and maternal care

Ensuring the protection and care of healthcare workers

MAKING THE CASE

The issue

Women are estimated to represent 70% of the global health and social care workforce,26 and are more frequently involved in care of the sick inside the household. The safety and security of health and social care workers is paramount for themselves and the people and populations they care for, including during a pandemic.27

Evidence for the role that gender plays

WHO has warned that without adequate consideration of women in the design of personal protective equipment (PPE), the protection offered for women can be compromised.28

The impact of working on the frontline may also be taking a heavy toll on health workers’ own wellbeing: a rapid systematic review of studies into the mental health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers found that women were more at risk of experiencing poor mental health outcomes than men.29

Interventions that take gender into account

Experience from other sectors where PPE is commonly used, have found that ‘traditional’ PPE is frequently designed for the male body, and PPE for women is often not widely available. By designing PPE in collaboration with women users, other sectors, such as the construction industry, have been able to redesign equipment and make it more acceptable to women in the sector.30

OUR FINDINGS

Findings from our review

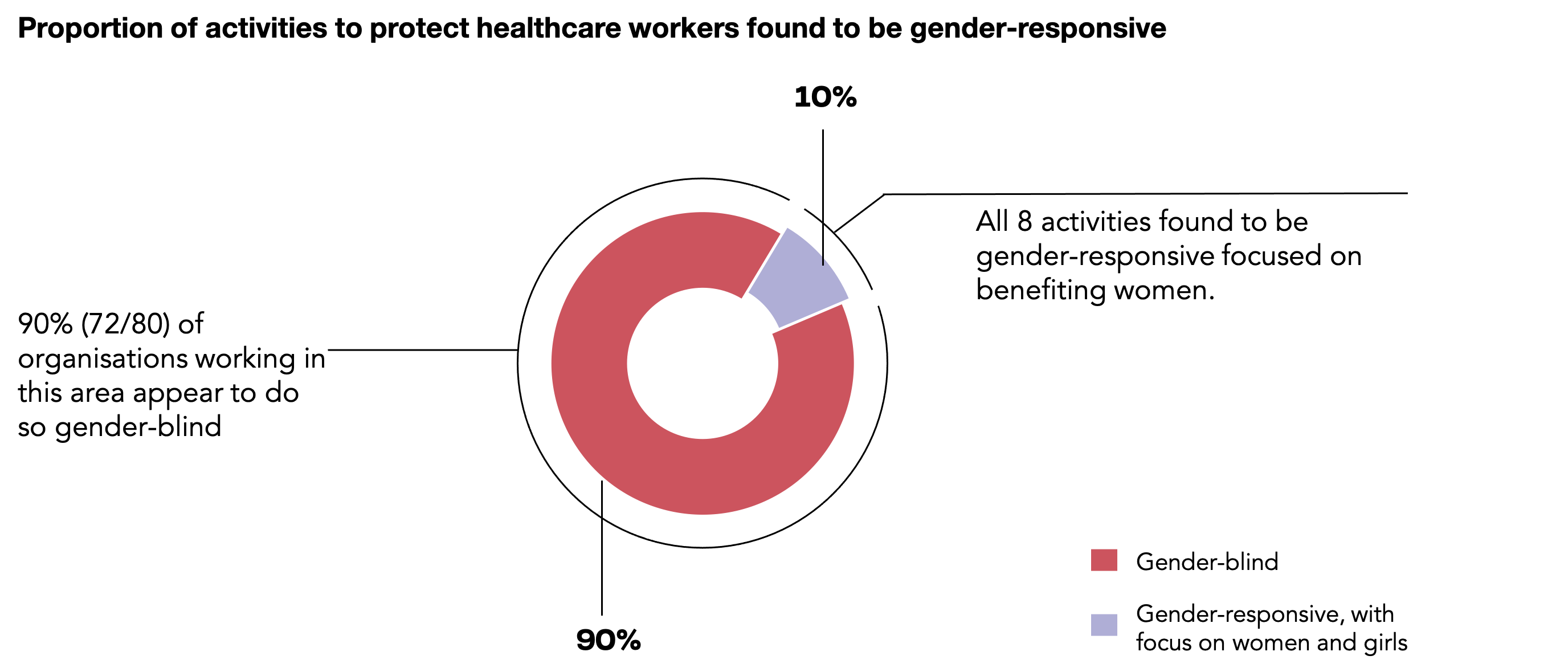

Among our sample, 80 organisations were found to be working on protection and care for health workers. Activities include distributing and issuing grants for PPE and hygiene products, providing guidance and training to frontline workers on infection prevention and control and establishing psychological support services.

Among these 80 organisations, 10% (8/80) described their activities with some level of gender-responsiveness while 90% (72/80) were gender-blind. Gender-responsive language included a recognition of the disproportionate risk of infection faced by women community health volunteers and directly targeting them with PPE provisions, and recommendations for policy-makers and investors on key gender responsive actions to be adopted in programmes targeting the health workforce.

All activities that specified their target population focussed exclusively on women healthcare workers.

Example of a gender-specific response to protection and care of healthcare workers during COVID-19

“Women have borne a heavy burden as frontline healthcare workers by taking on vital caregiving roles for COVID-19 patients. [...] These women face increased risks of infection, particularly when they work long hours without being provided with adequate personal protective equipment (PPE), or work in places where serious preventive measures are not taken.”

JICA commit to:

- Provide female healthcare workers and caregivers with necessary disinfectants and PPE, mental health services and psychosocial support, as well as reduce the burden of unpaid housework and domestic care work.

- Involve women in decision-making and have them represented in leadership positions within the healthcare and caregiving industry.

Japan International Cooperation Agency, Supporting female frontline healthcare workers31

Supporting national and global COVID-19 surveillance

MAKING THE CASE

The issue

Without sex-disaggregated data we will have an inadequate understanding of inequalities in the distribution of disease and insufficient knowledge of whether public health interventions are reaching all parts of the population equitably. Yet the Global Health 50/50 COVID-19 data tracker shows that just 70 out of 192 countries are presently publishing sex disaggregated data on both cases and deaths. Disaggregated data reporting is in urgent need of scale-up if we are to understand and address health inequities relating to COVID-19 in all countries.

Evidence for the role that gender plays

Sex-disaggregated data allows every organisation, country and health system to identify differences along the COVID-19 testing-to-outcome pathway, and to investigate how gender may be contributing to those differences. The World Health Organization recommends disaggregating data on testing, severity of disease, hospitalisation rates, recovery and health worker status at a minimum by sex and age, as well as by other social stratifiers such as socioeconomic status, ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity and refugee status.32 Collecting data on how these identities intersect is also important to understanding who is most vulnerable to adverse health outcomes.

Moreover, while we do not yet know the extent of gender bias in registration of COVID-19 deaths, historic bias in vital registration against individuals with fewer resources suggests that there may be an under-counting of female deaths in many countries.33

Interventions that take gender into account

Increasing rates of civil registration is essential for improving registration of deaths and cause of death. Physical access to civil registration sites, costs associated with birth registration and stigma towards single mothers can act as deterrents for vital registration among women.34 In Pakistan, for example, introducing mobile registration services staffed exclusively by women has increased accessibility for women and the Majoni scheme in India, which provided conditional cash payments to girls if they received birth registration, had a measurable improvement on birth certification rates in girls.35

OUR FINDINGS

Findings from our review

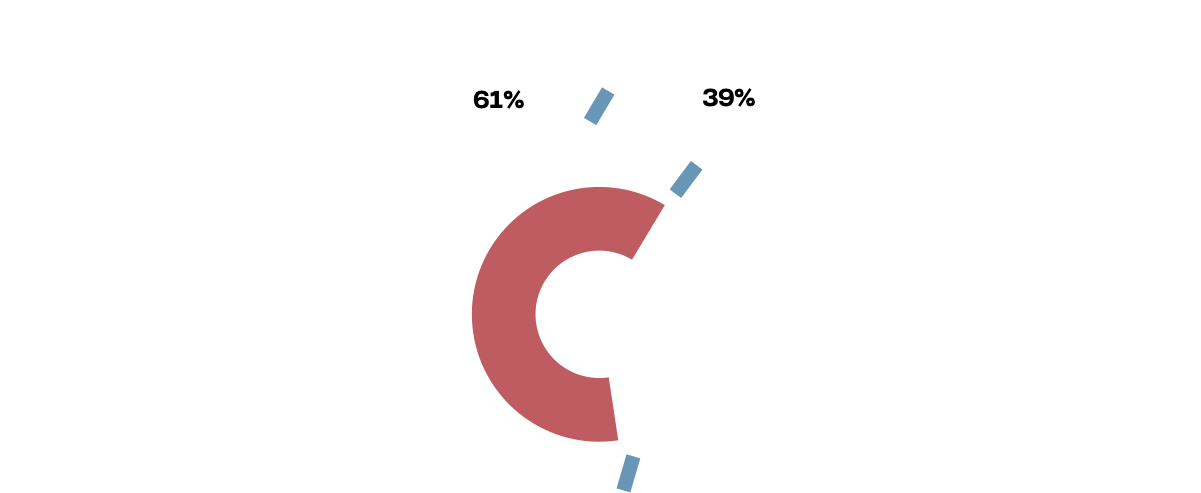

33 organisations were found to be supporting data collection and national surveillance of the COVID-19 pandemic. This included organisations that provide funding and technical assistance to strengthen national COVID-19 disease surveillance systems, training communities to be engaged in surveillance activities and conducting national level epidemiological studies.

Among these 33 organisations, 39% (13/33) reported or referenced sex-disaggregated data.

Example of a gender-responsive approach to COVID-19 surveillance

The International Center for Research on Women (ICRW) and the Africa Population and Health Research Council (APHRC), in partnership with Global Health 50/50, produce the world’s largest tracker of national sex-disaggregated data on COVID-19 health outcomes. Together, they examine the availability of sex-disaggregated data and collect, analyse and report on available data. They further advocate and engage government representatives and other stakeholders to strengthen commitment to the importance of analysing and reporting sex-disaggregated data to inform a more effective, equitable response to the pandemic.36

APHRC, ICRW and Global Health 50/50, Tracking sex differences in COVID-19 health outcomes and advocating for sex-disaggregated reporting

1 Scully, E.P., Haverfield, J., Ursin, R.L. et al. (2020) Considering how biological sex impacts immune responses and COVID-19 outcomes. Nature Reviews Immunology 20, 442–447

2 WHO (2020) 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Strategic preparedness and response plan https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/strategic-preparedness-and-response-plan-for-the-new-coronavirus

3 Crespí-Lloréns N, Hernández-Aguado I, Chilet-Rosell E. (2021). Have Policies Tackled Gender Inequalities in Health? A Scoping Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 18(1):327. DOI: 10.3390/ijerph18010327. PMID: 33466282; PMCID: PMC7796005

4 Shannon Olinyk, Andrew Gibbs and Catherine Campbell (2014). Developing and implementing global gender policy to reduce HIV and AIDS in low- and middle -income countries: Policy makers’ perspectives, African Journal of AIDS Research, 13:3, 197-204, DOI: 10.2989/16085906.2014.907818

5 WHO Gender Responsive Assessment Scale: criteria for assessing programmes and policies https://www.who.int/gender/mainstreaming/GMH_Participant_GenderAssessmentScale.pdf

6 Evelyne Bischof, Jeannette Wolfe, and Sabra L. Klein (2020) Clinical trials for COVID-19 should include sex as a variable. Journal of Clinical Investigation.130(7):3350-3352 https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI139306

7 Neumann-Böhme, S., Varghese, N.E., Sabat, I. et al. (2020) Once we have it, will we use it? A European survey on willingness to be vaccinated against COVID-19. The European Journal of Health Economics. 21, 977–982. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-020-01208-6

8 Paul, E., Steptoe, A., Fancourt, D. (2021). Attitudes towards vaccines and intention to vaccinate against COVID-19: Implications for public health communications. The Lancet Regional Health Europe. Volume 1 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2020.100012

9 Callaghan, T., Moghtaderi, A., Lueck, J. A., Hotez, P. J., Strych, U., Dor, A. Franklin Fowler, E. and Motta, M., (2020) Correlates and Disparities of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3667971

10 Morgan, R. and Klein, S. L. (2019). The intersection of sex and gender in the treatment of influenza.Current Opinion in Virology, Volume 35, 35-4 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coviro.2019.02.009

11 Zhao, M., Woodward, M., Vaartjes, I., Millett E. R. C., Klipstein‐Grobusch, K., Hyun, K., Carcel, C., and Peters, S. A. E. (2020) Sex Differences in Cardiovascular Medication Prescription in Primary Care: A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2020;9 https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.119.014742

12 Leslie, K. H., McCowan, C., Pell, J. P. (2019). Adherence to cardiovascular medication: a review of systematic reviews. Journal of Public Health, Volume 41, Issue 1, Pages e84–e94, https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdy088

13 Lehtinen M, Soderlund‐Strand A, Vanska S, et al. (2018). Impact of gender‐neutral or girls‐only vaccination against human papillomavirus‐results of a community‐randomized clinical trial (I). International Journal of Cancer;142:949‐958. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.31119

14 Abt Associates. Tracking COVID-19 in Pregnant Women and Infants https://www.abtassociates.com/projects/tracking-covid-19-in-pregnant-women-and-infants

15 Kelly R. Moran and Sara Y. Del Valle (2016). A Meta-Analysis of the Association between Gender and Protective Behaviors in Response to Respiratory Epidemics and Pandemics. PLOS One 11(10): e0164541. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0164541

16 Capraro, Valerio and Barcelo, Hélène. (2020). The effect of messaging and gender on intentions to wear a face covering to slow down COVID-19 transmission. 10.31234/osf.io/tg7vz

17 Vincenzo Galasso, Vincent Pons, Paola Profeta, Michael Becher, Sylvain Brouard and Martial Foucault (2020) Gender Differences in COVID-19 Related Attitudes and Behaviour Evidence from a Panel Survey in Eight OECD Countries. NBER Working Paper Series https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w27359/w27359.pdf

18 Elaine Vaughan and Timothy Tinker (2009) Effective Health Risk Communication About Pandemic Influenza for Vulnerable Populations. American Journal of Public Health 99, S324_S332, https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.162537

19 Conserve, D.F., Issango, J., Kilale, A.M. et al. (2019) Developing national strategies for reaching men with HIV testing services in Tanzania: results from the male catch-up plan. BMC Health Services Research 19, 317. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4120-3

20 Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (2020) A Gender Lens on our COVID-19 Response https://www.gatesgenderequalitytoolbox.org/wp-content/uploads/BMGF_GenderCovid_Investments.pdf

21 Penchansky, Roy D.B.A., Thomas, J William Ph.D (1981). The Concept of Access, Medical Care. Volume 19 - Issue 2 - p 127-140

22 Liana R. Woskie, Clare Wenham (2020) Do Men and Women “Lockdown” Differently? An Examination of Panama’s COVID-19 Sex-Segregated Social Distancing. medRxiv 2020.06.30.20143388; doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.30.20143388

23 FIND and Women in Global Health (2020) Discussion Paper: Testing, Women’s Empowerment and Universal Health Coverage https://c8fbe10e-fb87-47e7-844b-4e700959d2d4.filesusr.com/ugd/ffa4bc_d4bb9f64ca7d4890b571e8a79eb5f3f1.pdf

24 WHO (2020) Gender and COVID-19: Advocacy Brief https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/gender-and-covid-19

25 Audrey Pettifora, Sheri A. Lippmanc, Linda Kimarua, Noah Haberd, Zola Mayakayakab, Amanda Selind, Rhian Twineb, Hailey Gilmorec, Daniel Westreicha, Brian Mdakab, Ryan Wagnerb, Xavier Gomez-Oliveb, Stephen Tollmanb, Kathleen Kahnb (2020) HIV self-testing among young women in rural South Africa: A randomized controlled trial comparing clinic-based HIV testing to the choice of either clinic testing or HIV self-testing with secondary distribution to peers and partners. EClinicalMedicine DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100327

26 WHO (2019) Gender equity in the health workforce: Analysis of 104 countries https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/311314/WHO-HIS-HWF-Gender-WP1-2019.1-eng.pdf?ua=1

27 Alexandra Shaw, Kelsey Flott, Gianluca Fontana, Mike Durkin and Ara Darzi (2020) No patient safety without health worker safety, The Lancet. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31949-8

28 WHO (2020) Gender and COVID-19: Advocacy Brief https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/gender-and-covid-19

29 Ashley Elizabeth Muller, Elisabet Vivianne Hafstad, Jan Peter William Himmels, Geir Smedslund, Signe Flottorp, Synne Øien Stensland, Stijn Stroobants, Stijn Van de Velde and Gunn Elisabeth Vist (2020) The mental health impact of the covid-19 pandemic on healthcare workers, and interventions to help them: A rapid systematic review, Psychiatry Research, Volume 293, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113441

30 Milligan, Jarrett (2019). Inclusive Safety: Providing Tailor-Made PPE for Women. Professional Safety; Des Plaines Vol. 64, Iss. 8, 24-25.

31 JICA Guidance note: Establishing Gender-Responsive Approaches to COVID-19 Response and Recovery https://www.jica.go.jp/english/our_work/thematic_issues/gender/c8h0vm0000f9zdxh-att/COVID-19_01.pdf

32 WHO (2020) Gender and COVID-19: Advocacy Brief https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/gender-and-covid-19

33 UN ESCAP (2020) Unacounted deaths could obscure COVID-19’s gendered impact https://www.unescap.org/blog/uncounted-deaths-could-obscure-covid-19s-gendered-impacts

34 International Foundation for Electoral Systems and German Cooperation (2013) Survey assessing barriers to women obtaining computerized national identity cards (CNICs) https://aceproject.org/electoral-advice/archive/questions/replies/277728362/962062828/IFES-PK-Survey-Assessing-Barriers-to-Women.pdf

35 Jenita Baruah, Anjam Rajkonwar, Shobhana Medhi and Giriraj Kusre (2014). Effect of conditional cash transfer schemes on registration of the birth of a female child in India. South East Asia journal of Public Health. Vol 3 No 1. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3329/seajph.v3i1.17708

36 The Sex, Gender and COVID-19 Project. The COVID-19 Sex-Disaggregated Data Tracker https://globalhealth5050.org/the-sex-gender-and-covid-19-project/