Parental leave policies

Equitable paid parental leave policies are critical to fostering gender transformative norms of family responsibility, promoting women’s equality in career opportunities, compensating women for their reproductive labour, and closing the gender pay gap. Such entitlements further contribute to better recruitment results, higher employee morale and increased productivity, and benefit the health and wellbeing of families.

The extent to which leave policies deliver their potential benefits, including for career opportunities and progression, depends on the entitlements they provide. These include: the duration of leave; the wage replacement rate; whether leave, including shared leave, is made available to individual parents or is transferable; whether there is support available to new parents returning to work and at subsequent stages in the life of the child; the nature of leave when caring for dependents who are not children, and; support for flexible working arrangements for all staff.

The International Labor Organization's Maternity Protection Convention states that all countries, regardless of income, should guarantee women a minimum of 14 weeks of paid maternity leave. The World Health Organization, however, recommends at least 6 months (26 weeks) of breastfeeding, which is challenging for working mothers without adequate paid leave policies or lactation support in the workplace.

Despite calls for equality and universality, leave policies are frequently applied unequally or written in language that discriminates against or excludes some staff. For example, lengthy leave entitlements provided to women in the absence of similar entitlements for men can reinforce unequal parenting norms and harm women’s careers over the long-term. Disparate leave policies, when parental leave benefits for fathers are inferior to those for mothers, have on occasion been found in violation of equal employment opportunity laws.

Lengthy leave entitlements provided to women in the absence of similar entitlements for men can reinforce unequal parenting norms and harm women’s careers over the long-term.

Leave entitlements may also vary by the means of becoming a parent (childbirth or adoption). Additionally, leave entitlements for parents who are in same-sex relationships may not be recognised in the language used in some policies and therefore excluded from entitlements.

In response, we find that many national and workplace policies are moving away from gender-specific and unequal maternity and paternity leave, in favour of gender-neutral, equal and/or shared policies.

Some definitions

Findings: Parental leave policies

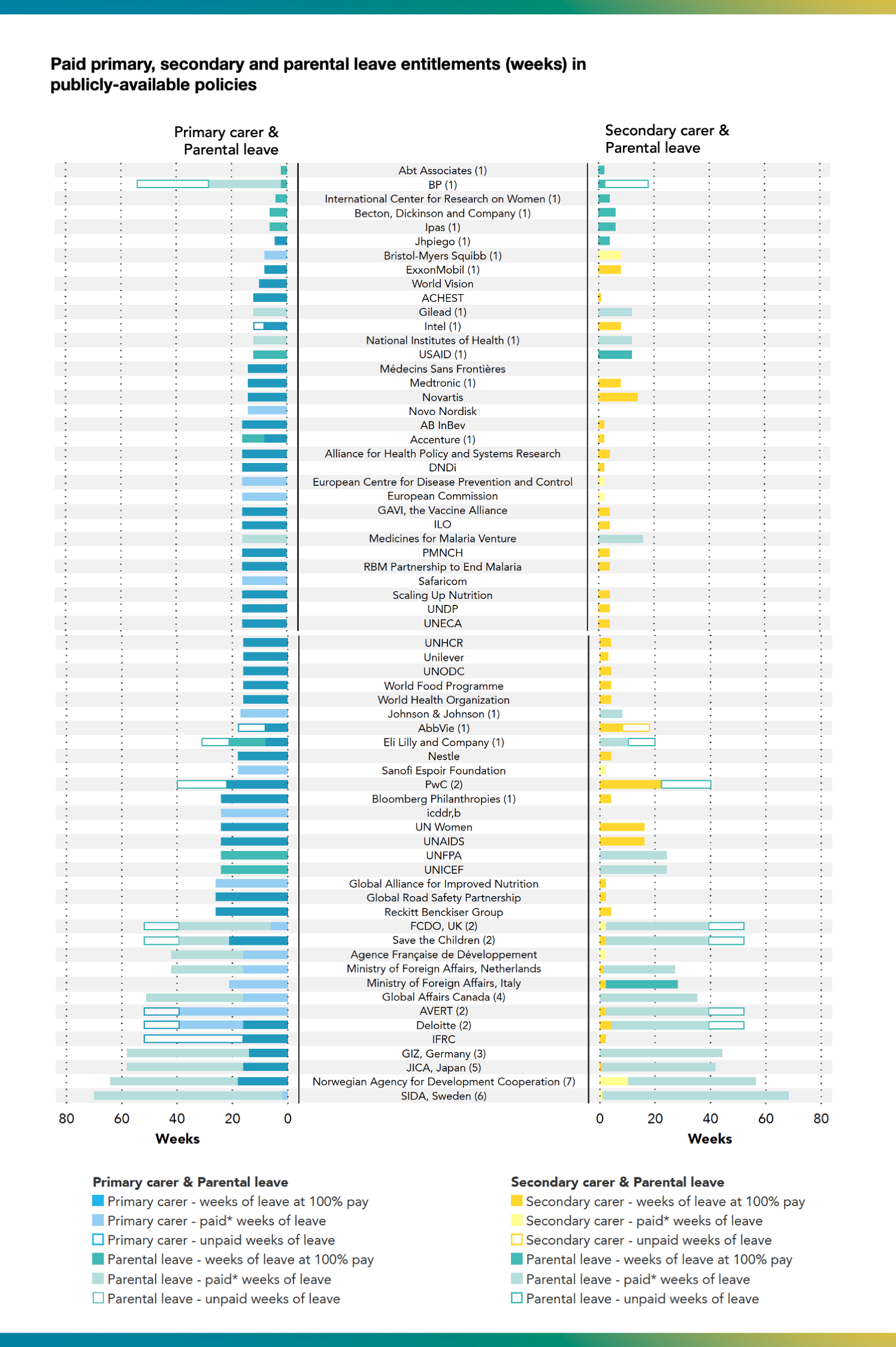

GH5050 assessed the number of paid weeks of leave available to primary and secondary caregivers as well as options for parental and shared parental leave. It also reviewed whether the organisation offers support to parents returning to work, such as flexible transitions back to work, reduced or part-time working hours, facilities for breastfeeding mothers, and/or childcare support.

33% (67/201) of organisations publish detailed information regarding their parental leave policies online. A further 46 shared their internal policies directly with GH5050.

Transparency of parental leave policies has improved since 2019, when GH5050 first reviewed them, with 57% of organisations making policies available for review overall in 2021 versus 39% in 2019. It is noted that some organisations with multiple country offices refrain from publishing parental leave policies as they may not be standardised across the organisation.

Transparency uptick: 17 organisations made their parental leave policies newly publicly available since 2019

The 113 policies reviewed vary widely, in part as a response to the standards set by national and sub-national legislation in the countries where the organisations are located. Among the 113 policies reviewed, guaranteed paid leave for primary and secondary caregivers ranges from zero to 68 weeks.

Organisations headquartered in Sweden, Norway and Japan were found to offer the longest leave benefits to both parents. While organisations in the US by and large offer the fewest number of paid weeks, they are almost uniformly offering the same benefits to both parents (gender neutral), with some additional paid leave for birth mothers covered by short-term disability insurance.

1 Depending on the employer’s policy, birth mothers in the US can also access short term disability (STD) for partial wage coverage for 6-8 weeks. Most if not all of the organisations in our sample offer STD benefits. Policies do not always specify where STD is already included in the number of weeks of paid leave available to birth mothers.

2 Employed mothers have the right to transfer all maternity leave to the father, except for the two weeks of obligatory leave, i.e. up to 50 weeks. This period of leave is termed ‘Shared Parental leave’ (SPL).

3 In Germany, parental leave is available up to three years after childbirth for each parent, of which 24 months can be taken up until the child’s eighth birthday.

4 Parental leave in Canada is shared.

5 Parental leave in Japan is shared.

6 Parental leave in Sweden is shared.

7 Parental leave in Norway is shared.

* Paid at less than 100% wages; Pay dependent on length of service; Paid but level of pay not indicated in policy

Findings: Support to new parents

Ninety-six (96) organisations indicated in their policies, or informed GH5050, of the support they offered to new parents in returning to work. Alongside entitlements of returning to a previous post (or equivalent) after a period of leave, some organisations offer support to returning parents in the form of, for example, opportunities for flexible working, provision of private spaces/time for lactation, shipping breastmilk when travelling on business, on-site childcare and/or financial support for childcare options. Some organisations also offer specific programmes including career coaching, expert advice, and dedicated personnel and resources to support back-to-work transitions.

Abt Associates monitors and reports on the proportion of women and men staff who return to work following parental leave and who are still with the company 12 months later.

PATH “is committed to supporting employee family responsibilities by offering parental leave policies, additional leave options for new parents, flexible work and resources for parents through our employee assistance provider.”

Access findings on organisations’ policies

To access detailed findings on organisations’ parental leave policies, go to: https://globalhealth5050.org/2021-detailed-findings/

Findings: Flexible working arrangements

As has been made starkly visible in the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, major caring responsibilities (including attending to elderly or sick or disabled relatives) are not equally or equitably divided across society. The major burden of home-care and home-schooling responsibilities, for example, have fallen on women. For many, employee control over how many hours they work and when has become essential. Even apart from the impact of the pandemic, younger generations are entering the workforce with expectations of greater flexibility, autonomy and work/life balance than their predecessors.

As workplaces have evolved over the past two years, reference to flexible working as a benefit has grown quickly. This growth appears to be independent of the requirement for many employees to work remotely in 2020/2021 due to COVID-19 lockdowns.

53% of organisations (107/201) report, either on their website or directly to GH5050, flexible working arrangements are available to employees. This is compared to 30% in 2019.

This figure does not take into account the situation in countries where flexible working is governed by national law. In the UK, for example, all employees have the right to request flexible working. Our finding represents those organisations where GH5050 was able to find mention of flexible working on the organisation’s website or policy.

53% of organisations report having flexible working arrangements available to employees - compared to 30% in 2019.

Some organisations reported that while flexible arrangements were available to staff in some offices, particularly in the US and Europe, these were not in practice across all country offices, in part due to local laws and culture. However, others reported that, building on lessons learned during office closures and restrictions under COVID-19, organisations intended to maintain flexible working arrangements that had been put in place, including in countries where flexible working was not yet the norm.