Findings: Gender parity in senior management and governing bodies

The demographics of who holds positions of authority provides a strong measure of the progress organisations are making in fostering equity in career advancement, decision-making and power. As such, it is a reflection of the performance of the sector across other areas of this report.

In many ways, the professional world operates at the end of a long pipeline littered with obstacles for many people. But organisations can decide whether to passively reinforce or actively seek to correct historical disadvantage and inequality—both to meet their obligation of contributing to a more equitable world and to shape more inclusive, effective workplaces.

Findings

Results show positive movement towards equal representation of women and men in senior management. The proportion of organisations achieving parity (45-54% women) increased by 8% in one year, from 28% in 2020 to 36% in 2021. In contrast, governing bodies that reached parity increased by 3% (to 29%) over the previous year.

Eleven organisations had no women in senior management and ten organisations had no men.

Making connections:*

Woman CEOs are 5x more likely to lead organisations with gender parity in senior management, compared to organisations led by men.

Women CEOs are 2x more likely to lead smaller organisations (under 250 staff) than larger organisations.

Smaller organisations (under 250 staff) are 8x more likely to have gender parity in senior management than larger organisations.

Reflection from the International Planned Parenthood Federation on gender parity in senior management:

A higher proportion of women in senior leadership is deliberate, informed and critical

We believe that to achieve parity one day, today, global health organisations should have more women than men in positions of leadership. This is because women make up the majority of the workforce in many of our organisations and the majority of our service users. Most importantly, we must promote women at the top with determination because the gap everywhere is so large.

Our gender equality policy recognises that progress requires transformative actions to promote women’s rights and empowerment, including addressing gender gaps, unequal policies and discrimination that have historically disadvantaged women and girls.

IPPF is committed to promoting feminist leadership at all levels of the organisation, which is critical for role modelling and for addressing inequalities that impact underserved individuals and communities. This leadership is reflected in our diverse board of trustees, which is inclusive of women and young people across geographies, genders, sexualities and abilities.

Findings: Gender and geography of CEOs and Board Chairs

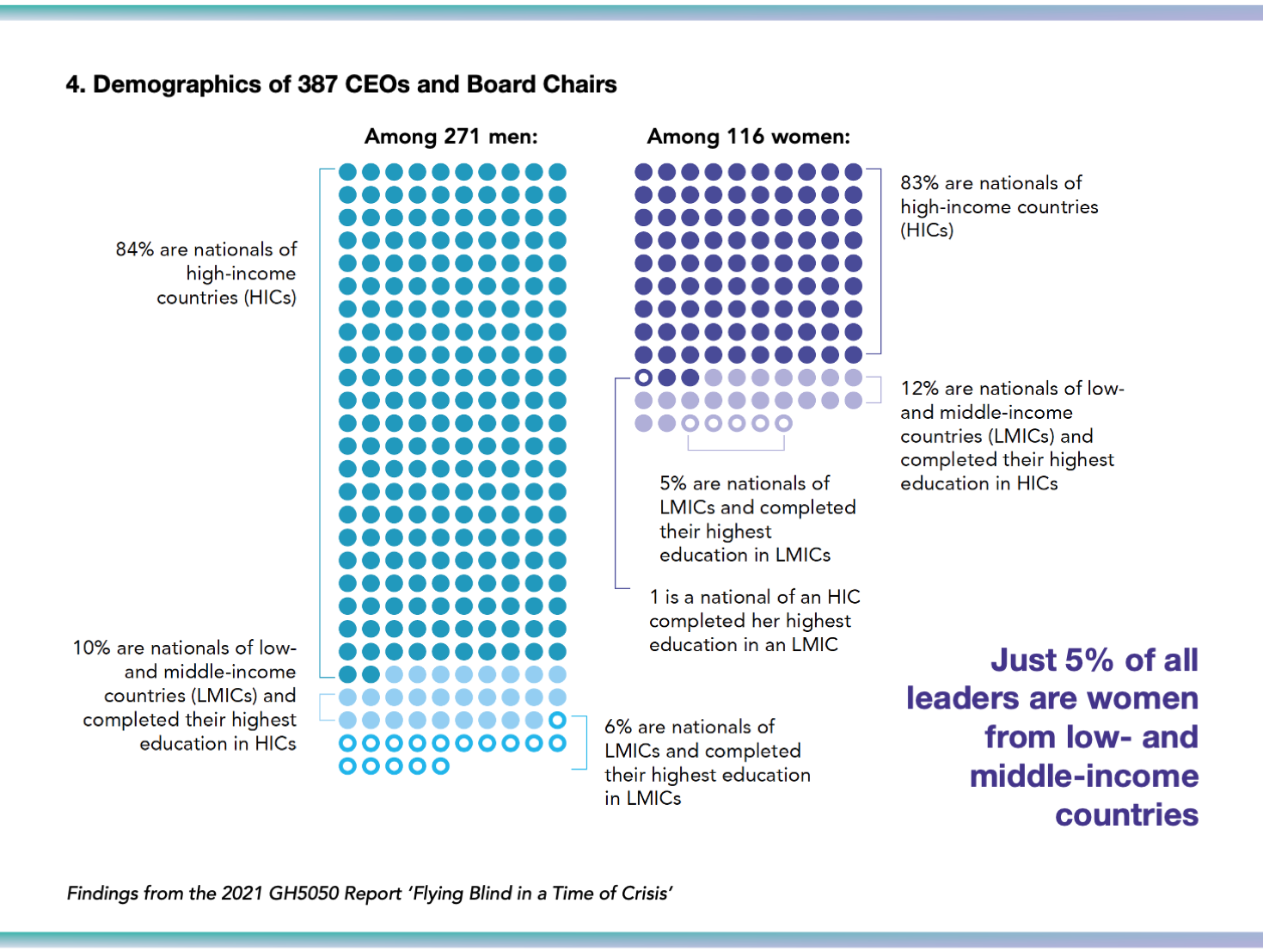

In order to capture the intersection of gender with other characteristics, GH5050 gathers publicly available demographic information on the CEOs and Board Chairs of the 201 organisations in the sample. This information includes: nationality, highest educational degree attained, university where that degree was attained and approximate age. These proxy measures provide insights into who holds power and privilege in global health.

While organisations are increasingly committed to gender equality and putting policies in place, the impact of these good intentions is only slowly being translated into the redistribution of opportunities and outcomes for people.

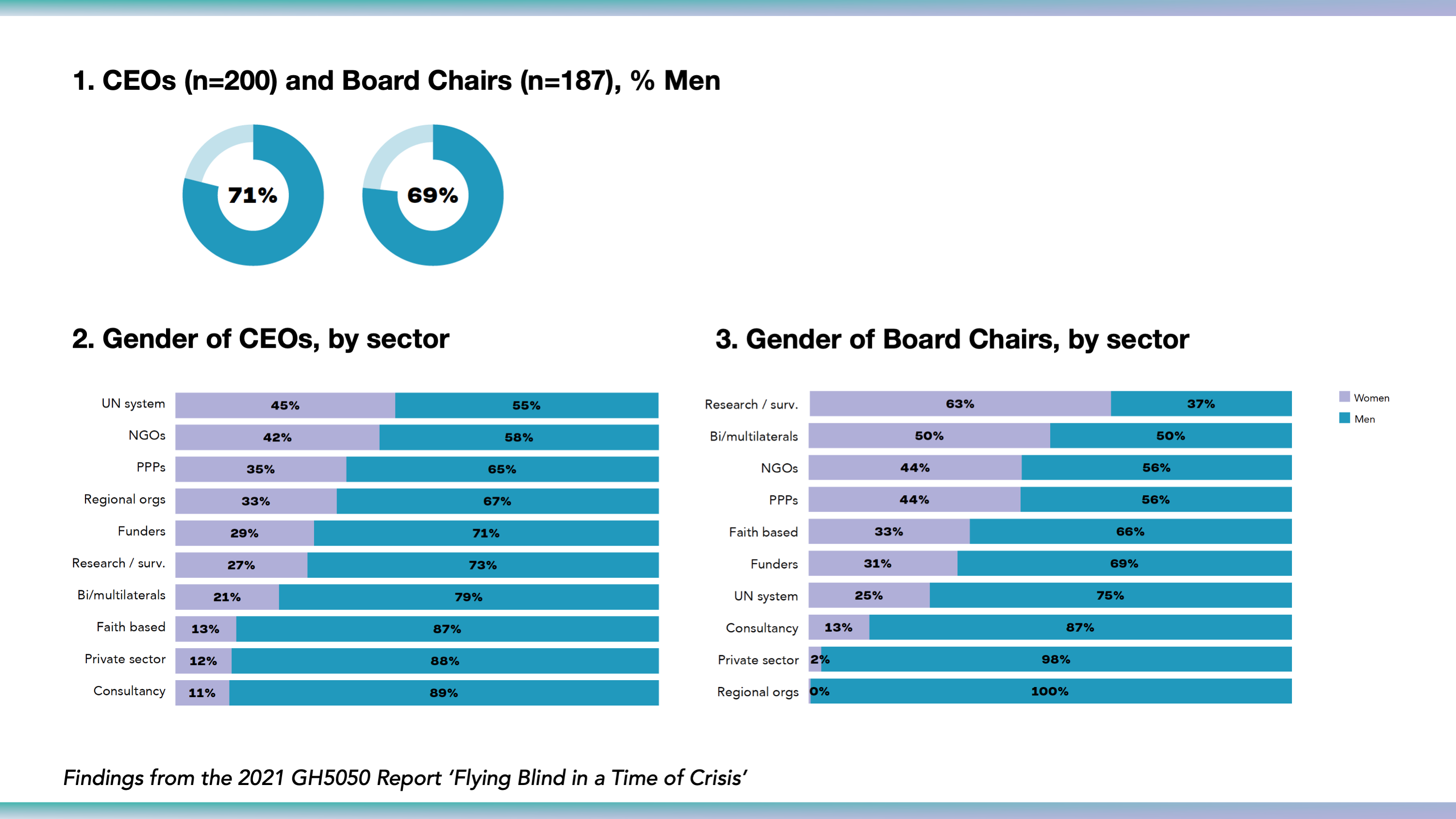

For the last four years, the proportion of organisations headed by women has barely changed. This is despite notable progress towards parity in senior management. In 2021, 71% of CEOs in the sample were men, and 69% of board chairs were men.

Among the sample of 139 organisations consistently reviewed since 2018, the proportion of male CEOs remains relatively unchanged, from 70% in 2018 to 69% in 2021. More Boards are chaired by women in 2021 than in 2018, but women are still far outnumbered by men. 28% of board chairs were women, compared to 20% in 2018.

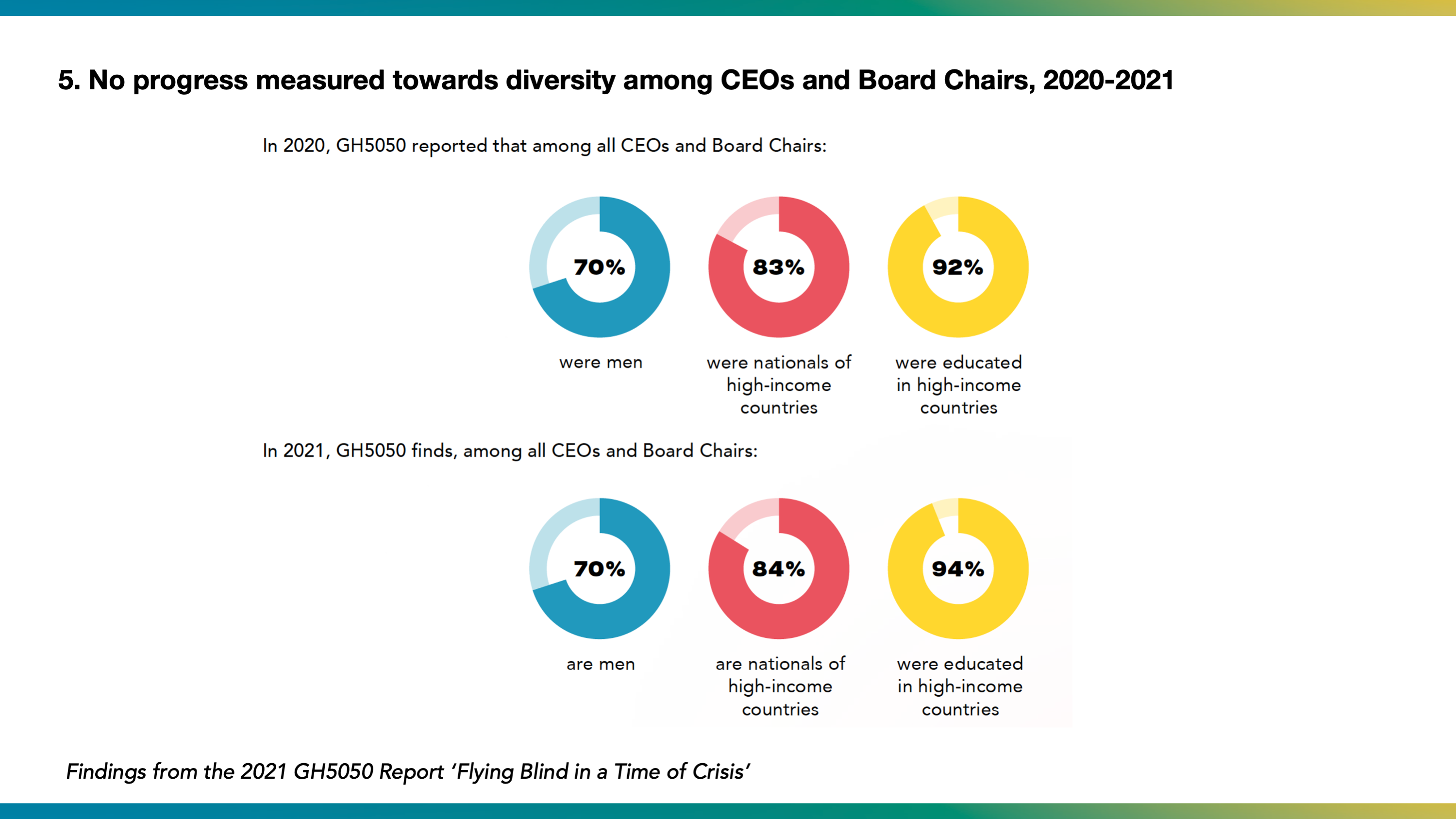

The 70-80-90 ‘glass border’ persists:

70% of leaders in the sample are men,

84% hail from high-income countries and

94% attained their highest education in high-income countries.

“We already know that diverse leadership culminates in better outcomes, so when we fail to include women, when we fail to include nationals from LMICs, we in essence, fail our communities.”

Siki Kigongo, Communications Manager, Africa Population and Health Research Centre

“As a woman from an LMIC and an immigrant, what I would like to see over the next 10 years is a global health sector that values true representation, and not just simply inclusion...I would also like to see a knowledge shift, so that knowledge is not just simply flowing from high income to low- and middle-income countries, but flowing multilaterally.”

Yadurshini Raveendran, Co-Founder, Duke Decolonizing Global Health Working Group

Given time, will diversity improve?

Spotlight on new leaders in 2020:

Demands to topple power and privilege imbalances and bring forth greater diversity in leadership reached new heights in 2020. Public statements were issued from leaders recognising systemic inequalities and vowing to take action. New diversity and inclusion commitments proliferated. Yet, when confronted with an opportunity to put action to words, the sector barely budged.

In the past year, more than 1 in 5 organisations (43/201) had a new CEO. Such turnover presents an opportunity to redress gender imbalances at the top. Such opportunity however was only partially seized: 70% of outgoing CEOs were men -- as were 66% of new appointees.

A total of 94 new CEOs and Board Chairs were appointed over the last year. In positions vacated by women, 54% of new appointees were women. However, in positions vacated by men, 74% of their successors were male. Overall, among the 94 new CEOs and Board Chairs appointed, women gained six positions.

If demographic trends among new cohorts of leaders continue, many in the sector will not see parity in their lifetime. Yet if 52% of new leaders appointed each year were women, parity could be achieved by 2030.

If 52% of new leaders appointed each year were women, gender parity at the top could be achieved by 2030.

“Leaders and boards of organizations must re-imagine benchmarks to advance equality within organizational leadership...At the same time, leaders hailing from prestigious universities and high-income countries need to become comfortable listening and creating space to be challenged and to receive grievances.”

Jaya Gupta, researcher and member of the Global Health 50/50 Collective