Findings: Workplace diversity and inclusion policies

The majority of organisations under review operate in countries with legal frameworks that protect workers against discrimination, including equal employment opportunity laws and equal pay laws. Yet, while such laws are essential, they are insufficient to level the playing field when individual bias and institutional discrimination continue to reinforce existing systems of power.

For organisations which have entrenched power asymmetries, addressing equality needs to go further still and delve into the past, interrogating historical injustices, identifying how they are perpetuated through existing power structures, and taking action. For example, this could mean putting specific measures in place to support the careers of historically underrepresented groups.

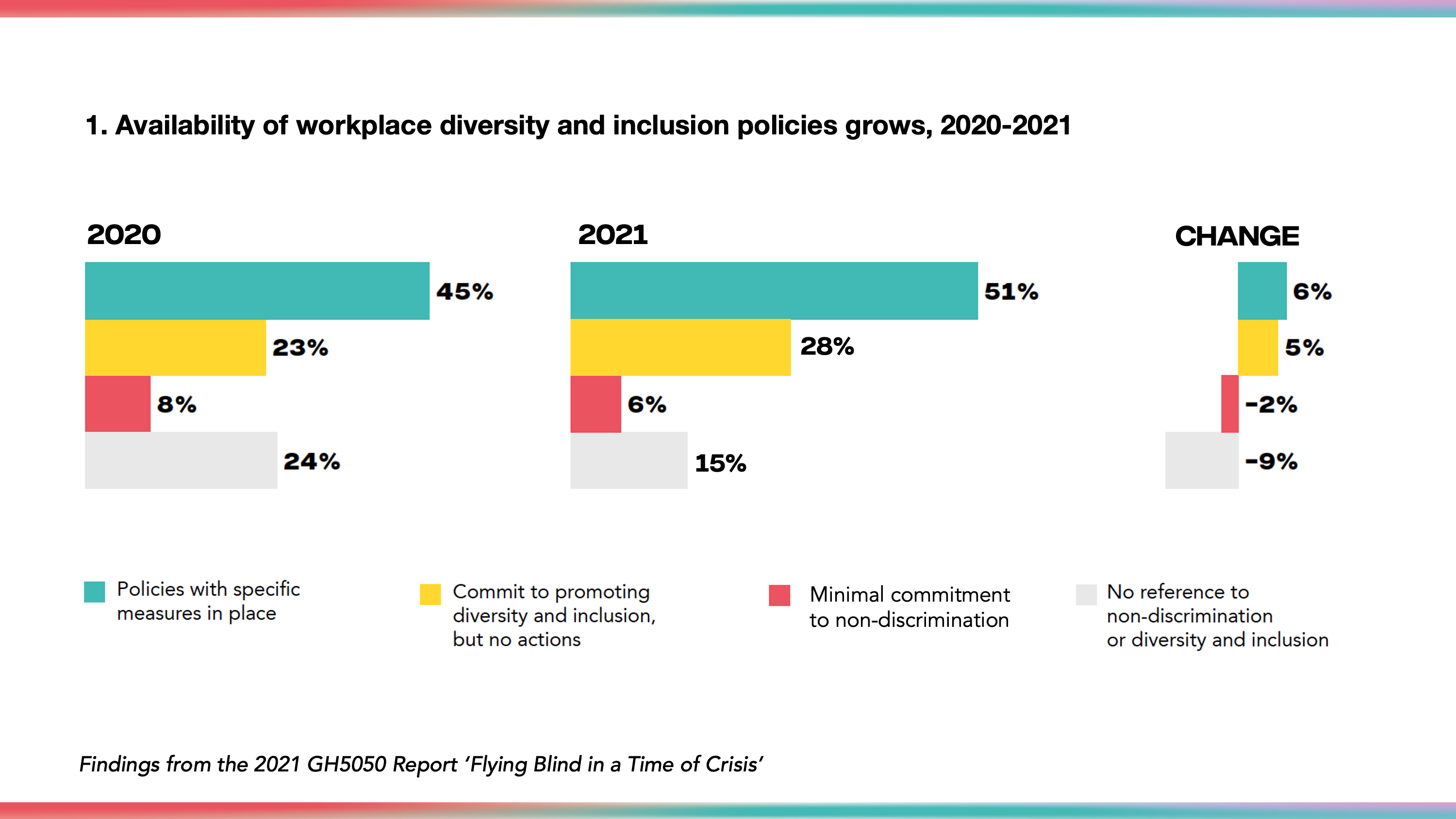

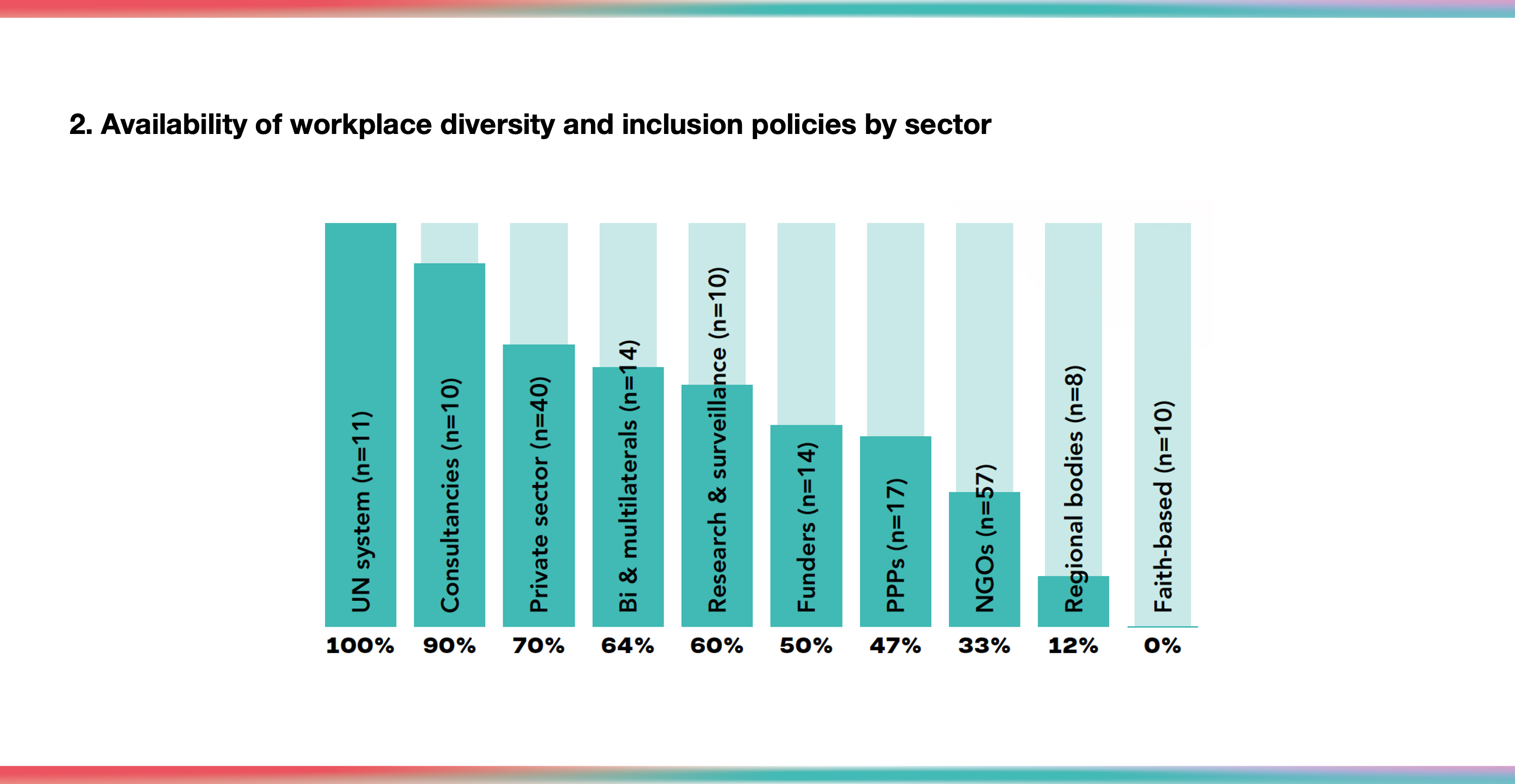

Advancing diversity and inclusion requires clear policies, deliberate focus, sustained action, and accountability. GH5050 assessed which organisations (with more than 10 employees) had publicly available policies that committed to advancing diversity and inclusion in the workplace—alongside and beyond gender equality—and had specific measures in place to guide and monitor progress.

Findings

Policies to advance diversity and inclusion—beyond gender—in their workforce were identified for 51% (98/191) of organisations. The proportion of organisations making reference to diversity and inclusion increased from 68% to 79% in the past one year.

Several organisations incorporated recognition of the role of structural inequalities and injustice in contributing to the underrepresentation of certain groups, particularly at senior levels. With such recognition, the most comprehensive policies then move beyond commitments to non-discrimination and towards anti-discrimination practices that aim to actively redistribute opportunity.

“Systemic racism is built into the fabric of many American institutions in addition to policing and structures of power. The healthcare system disproportionately fails Black and Brown communities; they are disproportionately being infected and killed by COVID-19. As a global health organization, we know that inequity, discrimination, racism and violence directed at any community are all social determinants of poor health. They result in deadly circumstances, whether in the 50 formerly colonized countries where we work or here in the US. We’ve committed to doing what is different and difficult for change in those countries. We commit to doing it here for our employees as well.”

Population Services International, https://www.psi.org/2020/06/a-statement-of-psi-solidarity/

Examples of measures organisations are taking to advance on their commitments to diverse and inclusive workplaces:

- Targets for leadership teams and governing bodies to comprise no more than two-thirds of one gender; targets to improve ethnic diversity in leadership positions.

- Monitoring the gender and diversity composition of human resources at all levels (governance, management, staff, volunteers), and analysing in light of potential barriers to equal opportunities, diversity and inclusion related to power and decision making.

- Producing resources and FAQs for LGBTQ+ staff working overseas, including on issues of safety, security and support networks.

- Producing transgender inclusion guidelines and allyship for all staff, including rationale of adding pronouns to email signatures.

- Institutionalisation of D&I capacity in the form of offices, senior staff with specialised expertise, and ombudspersons.

- Formation of staff D&I committees and resource groups, with mandates that range from monitoring recruitment and selection processes, to facilitating and accelerating the personal development and professional advancement of underrepresented groups.

- Mandatory inclusion training, which is helping to increase awareness and understanding of inclusion and diversity, highlighting what exclusion and bias is and how to prevent it.

- Explicit inclusion of part-time workers in diversity and inclusion plans as well as ensuring their access to leave benefits, professional training, and furlough programmes.

- Annual D&I transparency reporting on progress towards defined metrics, including composition and compensation by race, gender and other characteristics.

- Undertaking third-party, independent gender and D&I audits.

Access the policies

To access all publicly available diversity and inclusion policies and plans that were reviewed this year, go to: https://globalhealth5050.org/2021-policy-links

Findings: Board diversity and inclusion policies

Globally, demands for gender equality and broader diversity on boards are loud and growing, bolstered by evidence that diverse and inclusive boards are more innovative and effective. Boards of directors are arguably the most influential decision-makers in global health. They often nominate an organisation’s leadership. They help to determine goals and strategy. Yet continued lack of diversity in boards means that they are missing the perspectives of key stakeholders, including the communities they are meant to serve.

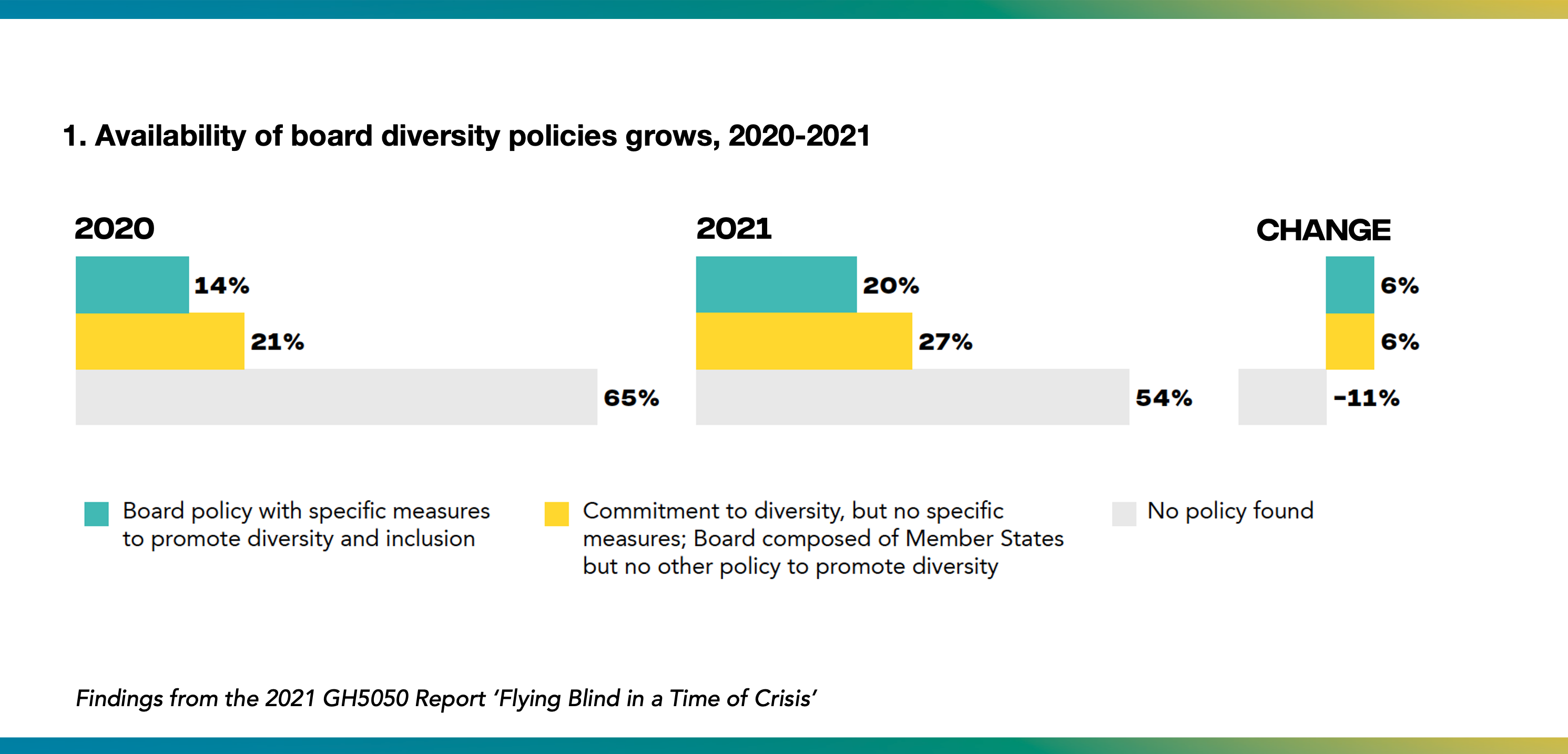

GH5050 reviewed which organisations had policy statements online on advancing diversity and inclusion and/or representation of affected groups in their governing bodies.

Findings

20% (39/199) of organisations that appear to have governing bodies have policies available in the public domain that indicate how they seek to advance diversity and representation in those bodies. This marks a moderate increase since 2020.

The proportion of organisations that commit to diversity and representation in their governing body increased from 35% to 46% in 2021.

Growing commitment: Proportion of organisations committed to diversity and representation in their governing body increased by 11% in one year.

“We want to ensure that we achieve a 40% ratio of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color on our board. Currently 39% of our Board identifies as Black, Indigenous, or People of Color. We also are committed to a Board that is gender balanced, with 50% identifying as women, in keeping with our identity as an organization centering its work on women and girls (currently we are at 46% identifying as women).”

Care USA, https://www.care.org/about-us/equity-and-inclusion/

The composition of a number of organisations’ governing boards is determined by country affiliation, rather than individual appointees, which means that organisations themselves have no direct authority over who sits on the board. This is the case for the UN system and several regional political bodies. Many of these organisations however still support and encourage Member States to pursue gender parity in delegations, including by tracking and reporting gender representation, e.g. by the International Labor Organisation, UNAIDS and World Food Programme.

“The Governing Body: (a) urged all groups to aspire to achieve gender parity among their accredited delegates, advisers and observers to the Conference and Regional Meetings; (b) requested the Director-General, after every Conference as well as Regional Meeting, to continue to bring the issue to the attention of Members and groups that had not reached the minimum target of 30 percent of women’s participation with the goal of gender parity, and to periodically report to the Governing Body on obstacles encountered, as well as measures taken by tripartite constituents to achieve gender parity.”

United Nations General Assembly Resolution 58/142 (2003) on ‘Women and political participation’ urges States to “promote gender balance for their delegations to United Nations and other international meetings and conferences.”

Decision of the 2018 ILO Governing BodyInvesting in organisational change: the role of funders

Increasingly, investors are considering not just what they fund, but who they fund—and how their resources can catalyze social change both through and within their grantees. As a core practice in influencing a more gender equal and diverse global health sector, funders should consider leveraging funding to enable organisations to move from commitment to action by resourcing workplace gender, diversity and inclusion work—particularly for organisations who may not otherwise have the capacity or finances to do so.

Investing in institutional capacity to advance equity, diversity and inclusion should no longer be considered optional. It is an essential competency for any effort that aims to meaningfully engage in the diverse complexity of our societies.Access the policies

To access all publicly available governing board diversity policies and plans that were reviewed this year, go to: https://globalhealth5050.org/2021-policy-links